Thinking in Systems

by Donella Meadows

- Nonfiction

- Shelves: science, psychology, environments, systems, economics, design

- 240 pages

- ISBN: 9781603580557 (Goodreads)

- Format: Kindle

- Buy on Amazon

Summary

Humans have a tendency to view the world as a series of events, a chain of causes and effects, rather than the intertwined, complex web of connections it actually is.

Thinking in Systems is what it says on the tin: a short, succinct primer on systems thinking, which is a way of looking at the world that attempts to more accurately model the relationships between elements. Fundamentally, a “system” as Meadows defines it is any combination of elements joined through interconnections for some function or purpose. It’s a broad concept, but once you start visualizing systems this way, it’s easier to follow the complex chain of second and third order effects that can arise when an element or interconnection changes within a system.

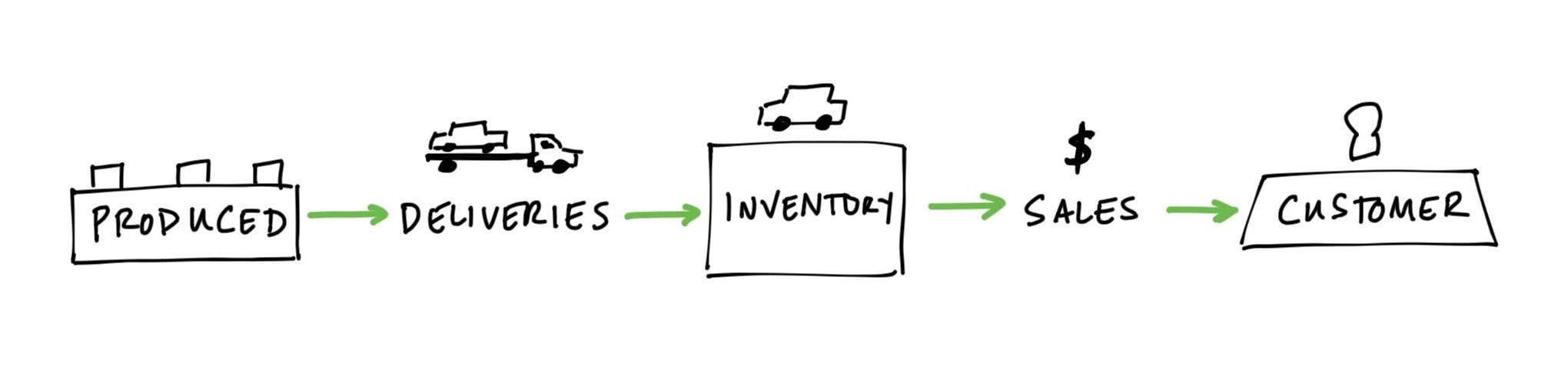

To use an example from the book, looking at a system for producing and selling cars, one might draw a diagram like this to represent the system’s elements and connections: a simple linear cause/effect series of steps moving from production at a factory through to sale to a customer:

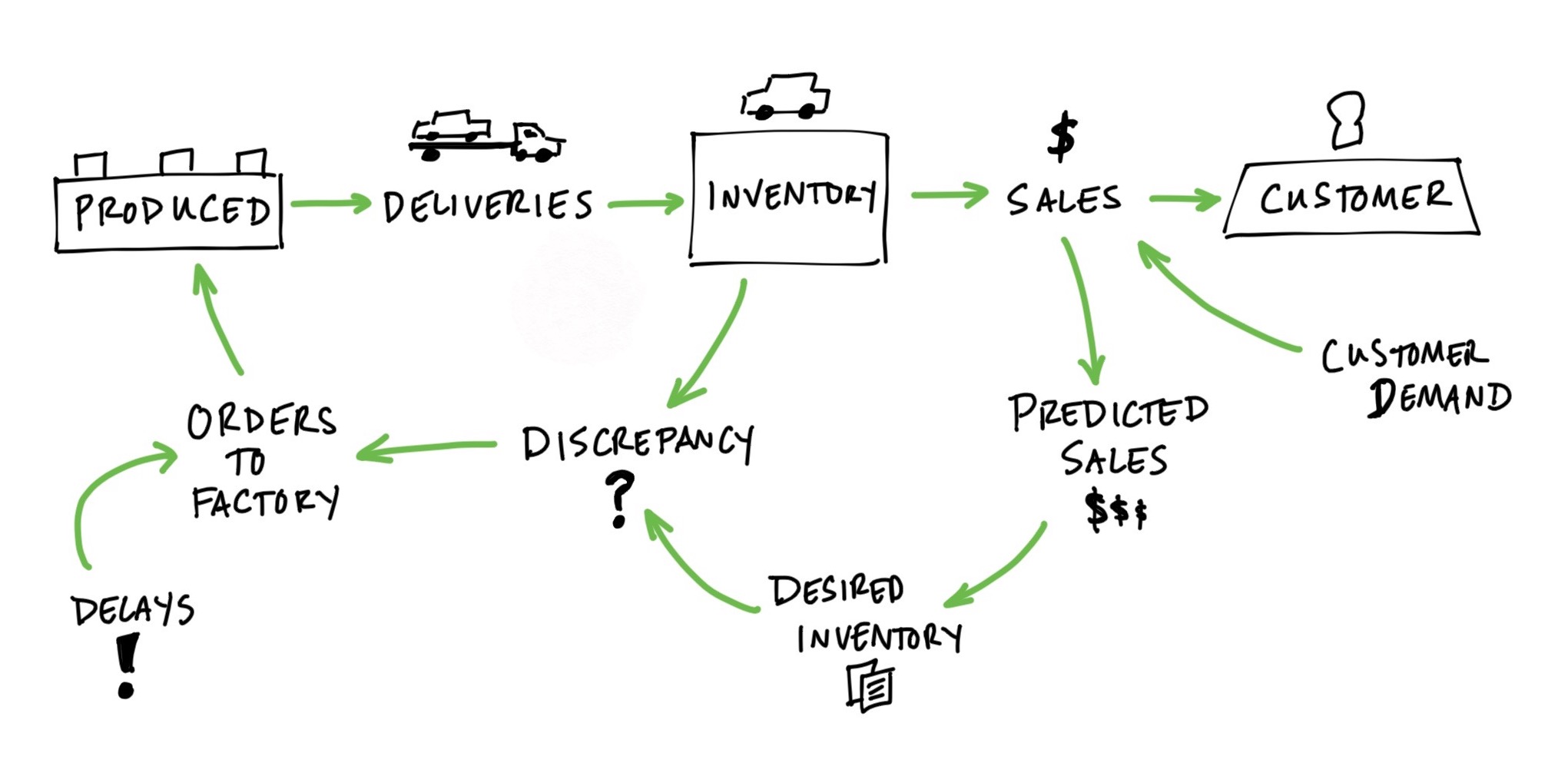

But if we peel apart the different feedback loops at play in the system, we get something much more complex (and even this is a simplification):

With systems thinking, we look at systems as related, nested feedback loops, not cause and effect models. The foundational units are stocks, fixed volumes you can see, measure, and count, and flows, which represent the filling or draining of stocks. So a bank balance is a stock, and deposits and withdrawals are flows.

Critical to systems also are feedback loops which essentially come in 2 varieties: balancing loops, which keep stocks in check, and reinforcing loops, which have self-enhancing, compounding effects. So in our banking example, spending money has a balancing effect, and interest earnings have a reinforcing effect.

When analyzing a system either to correct or optimize, there are some rules of thumb about systems behavior that come in handy. For one, you can adjust flow rates more quickly than you can adjust stock volumes. This is because, due to the nature of inertia, stocks have “mass” to them that’s difficult to move rapidly, you must make a change to an inflow or outflow in order to change the stock level, which takes time. But because of this, we can actually use this delayed feedback to our benefit if we understand it. Stocks act as buffers or shock absorbers that permit you to experiment with the system structure through tweaking inflows and outflows without necessarily causing instantaneous shockwaves throughout the entire system. If you have a bank balance of $50,000, you can spend marginally more or less money in a given month without a substantive change to your lifestyle, you just can’t do this forever. This shock absorption phenomenon permits the experimentation needed to make continued improvements without attempting whole-cloth, ground-up redesigns of entire systems (a problematic endeavor, to be sure).

There are a couple of other interesting observations and rules of thumb to keep in mind. One is the notion of dominance: if a balancing or reinforcing loop’s associated flows increase or decrease too much, it can overtake other loops in its influence on the overall system, dominating or negating the effects of other subsystems. Many of the strange dynamics we observe in real-world complex systems are the result of shifting dominance, where loops drive runaway growth or encumbering drag that causes wild changes in expected results.

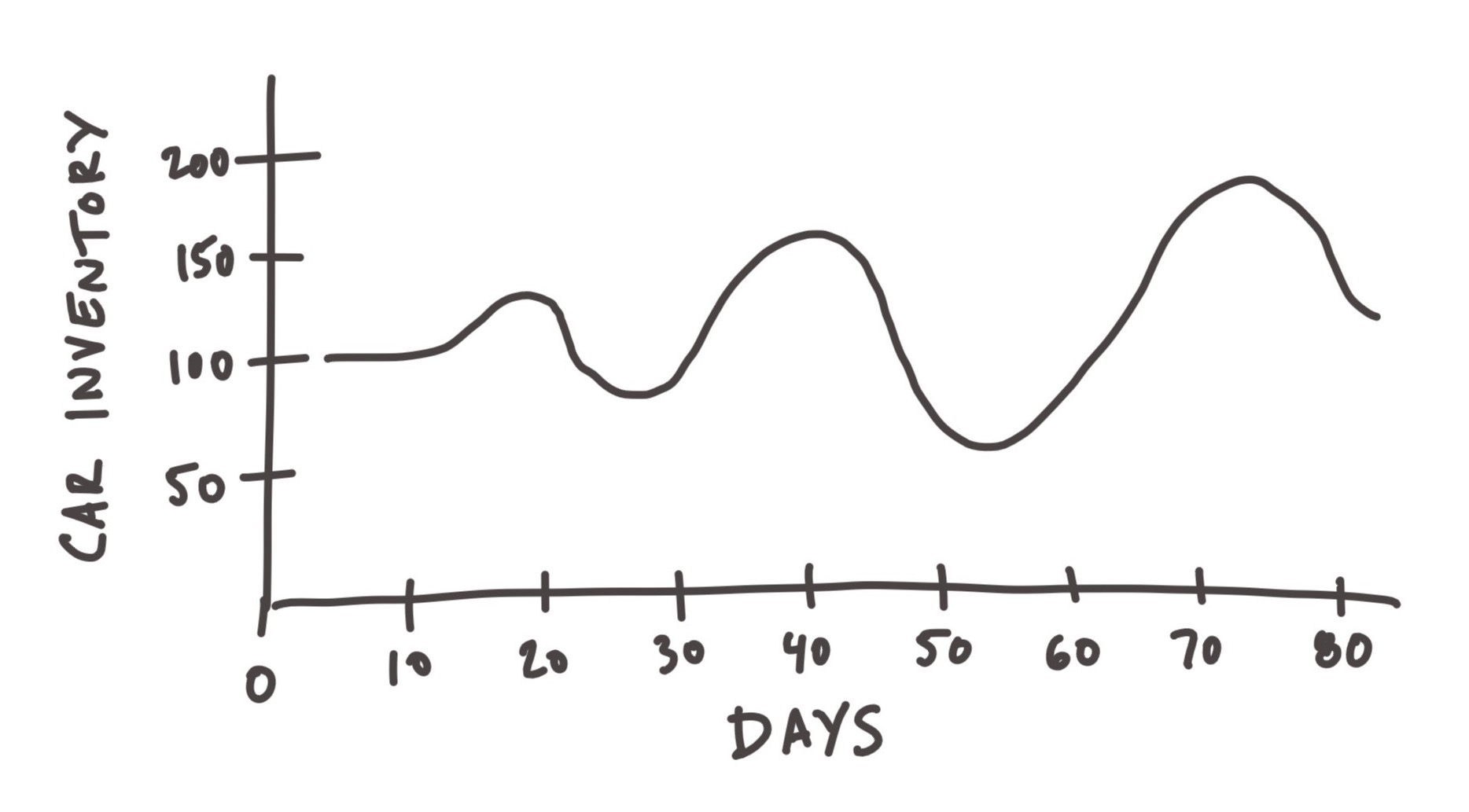

It’s also helpful to understand the impacts of delays in feedback loops. If delays are long enough, and combined with enough swing in the changing inflow/outflow volumes, you can see oscillations in the overall system. An example from the book talks about delays in the vehicle sales supply chain:

When a car dealer notices an upswing in order flow, they order more cars from the maker. But because it takes time for those deliveries to be made, in the meantime order flow may have slowed down in subsequent months, leaving the dealer with an inflated inventory. The dealer may then halt new deliveries from the maker, but then deplete too much stock. Delays in multiple feedback loops cause rubber-banding oscillations in the stock volume and flow rates.

Meadows spends a decent chunk of the book making a case for resiliency in systems, arguing for system designs that can withstand shocks and perturbations. Often reliency in system structures is sacrificed for stability or productivity. To use James C. Scott’s example of “scientific forestry” from Seeing Like a State (the purposeful planting of monocropped tree farms to maximize a very narrow set of measures, like total board-feet of lumber), intentionally-planted monocrops make productive output more predictable, and make it easier to maintain stability in “average” tree health, with roughly equal ages and sizes of tree. But indexing on each of these sacrifices resiliency: monocrops are much more susceptible to infestations, disease, fire, and other risks.

Because information holds systems together, transparency and information flow between subsystems is essential to a health and resilient parent system. A subsystem need not expose all of its neighboring systems to the complexities within it; an individual subsystem runs like an algorithm, and the outflow provided to the next subsystem functions as digestible packets of information. So in the diagram above on the sale of cars, predicted sales feeds a number to desired inventory — the handler of the next batch of orders doesn’t need to understand the internal prediction logic driving the request, it just needs to process a number. Since information is the currency of systems, an essential component of resiliency is transparency. If elements of the system shield, distort, or hide information, the negative effects cascade invisibly on through adjacent parts of the system. Two examples: bureaucracy and regulation are two forms of artificial throttling or accelerating of systems, putting fingers into the machinery of the system to influence it in some way. That’s not to say these two things are inherently evil, but they both have a tendency to shield components of the system from reality. A regulatory body might impose price controls, temporarily or permanently, on a good, like corn or wheat. With the producer unable to use market prices as a signal for downstream demand, a farmer produces a surplus which has no customer, leaving the government to buy and store (with perhaps no known use) the commodity so as to not bankrupt the producer they confused with incorrect signals. This sort of information distortion, often done with good intentions, then causes its own overcorrections and further distortions. Breaking out of the spiral can be extremely painful.

Astoundingly complex (and functional) systems can evolve from a trivial set of initial ingredients and rules. Self-organization derives from a set of simple rules that permit systems to evolve their own subsystems and internal behaviors. To get to resilient and self-organizing systems, though, it must start from a simple functioning system, and must be seeking the right goal.

The best example of self-organization comes from biology. All life on earth is formed from the same simple rule set: 4 amino acids (AGTC) combine into “words” of 3 acids each. These make up DNA, which permits enough diversity and variability within its simple modular architecture to create an astounding diversity of millions of species. What looks from above like disorder, through chance and experimentation, creates order and novelty. Self-organizing systems also establish their own hierarchy — nested groupings of subsystems that specialize to solve subproblems to the overall system. An organism is made up of organs, which in turn are composed from cells, which are composed from chemicals and molecules.

Complex systems can only arise from simple ones if there are stable intermediate forms. Hierarchical structure allows systems to solve particular problems at the right level, optimize for particular outcomes, then nest these together once stabilized to form stable wholes. I love this framing, and it makes perfect sense. Why would we expect unstable or unpredictable subsystems to produce predictable and stable results when interlocked together? Recall Gall’s law:

A COMPLEX SYSTEM THAT WORKS IS INVARIABLY FOUND TO HAVE EVOLVED FROM A SIMPLE SYSTEM THAT WORKED.

The parallel proposition also appears to be true: A COMPLEX SYSTEM DESIGNED FROM SCRATCH NEVER WORKS AND CANNOT BE MADE TO WORK. YOU HAVE TO START OVER, BEGINNING WITH A WORKING SIMPLE SYSTEM.

— John Gall, Systemantics

If we can’t drive stability at the lowest levels, we’ll only create chaos at a higher, more destructive level. Experiment and fail at the lowest level of the system.

The book steps through a number of “system traps”, common examples of poorly configured feedback loops and their results. We encounter familiar examples like the tragedy of the commons, rule beating, drift to low performance (the Broken windows theory), and seeking the wrong goal. Meadows steps through some great concrete examples of each with some helpful advice on how we might avoid or escape these traps. They’re traps because each one is inherently self-perpetuating. Without explicit intervention, each one will continue.

Meadows closes with a stack-ranked list of leverage points — places within systems where you can tweak, modify, or rebuild for maximum effect. The place we most often start when fixing system is the place she deems the least impactful: tweaking the numbers, constants like taxes, subsidies, or standards. We gravitate to these because they’re easiest to measure and easiest to change, but they have the least impact on the system’s behavior overall. Oftentimes a self-organizing system will find its way around whatever minor thread you pull buried deep within a system (see: any change to minor economic policy). There might be noticeable impact for a short time (say, a term of office), but a sufficiently complicated system will find methods of circumvention. The more impactful intervention points are things like opening up information flows (also one of the cheapest changes to make) and redesigning subsystems with self-organization in mind. This permits the necessary experimentation, exposes the overall system to the lowest risk to try things on for size, and allows those closest to their individual piece of the action to use their superior knowledge of their area to make corrections.

This is one worth keeping on the shelf and revisiting after a while. I’ve viewed things through a different lens ever since I read it, and here writing these notes a year later, reviewing the book again after looking at the world this way has made it even more tangible. The appendix is worth the price of keeping a copy. It’s got an excellent glossary and an archive of examples, mental models, and resources to call back to.

Key Takeaways

- Systems are sets of things interconnected in a way that they produce their own patterns of behavior over time

- They’re composed of 3 things

- Elements

- Interconnections — connecting elements

- Function or purpose — driving a result

- Components of systems

- Stocks — the foundational unit of a system, elements you can see, count, store, or accumulate over time

- Flows — the filling or draining of stocks through things like purchases/sales, growth/decay, deposits/withdrawals

- A stock is the present memory of the changing flows of the system

- We focus more readily on stocks than flows because they’re more visible, measurable, and comparable

- And with flows, we focus more easily on inflows than outflows

- Stocks act as delays, buffers, or shock absorbers in a system

- These time lags make space for experimentation

- They allow inflows and outflows to be decoupled; we can tinker with one without impacting the other immediately

- Systems thinkers view the world as a collection of feedback processes

- Types of feedback looks

- Balancing feedback loops — these temper or reduce the amount of accumulation in a stock

- Reinforcing feedback loops — drive runaway growth in stock volume if unchecked by balancing loops

- Systems behavior and archetypes

- Dominance occurs when one loop gains outsized influence on the system overall, reducing or even negating the effects of other loops

- Delays in feedback loops through a system cause oscillations and volatility

- Resiliency derives from simple, powerful base rules, and typically self-organizing effects of systems

References

- John Gall’s Systemantics

- Res Extensa #6: Stocks, Flows, and Feedback Loops

- Tobi Lutke, Building a Modern Business, Invest Like the Best

- Max Olson’s Advantage Flywheels

- Dancoland, Alex Danco