On Legibility — In Society, Tech, Organizations, and Cities

April 6, 2021 • #This is a repost from my newsletter, Res Extensa, which you can subscribe to over on Substack. This issue was originally published in November, 2020.

In our last issue, we’d weathered TS Zeta in the hills of Georgia, and the dissonance of being a lifelong Floridian sitting through gale-force winds in a mountain cabin. Last week a different category of storm hit us nationwide in the form of election week (which it seems we’ve mostly recovered from). Now as I write this one, Eta is barreling toward us after several days of expert projections that it’d miss by a wide margin. We’re dealing with last-minute school closures and hopefully dodging major power outages. 2020 continues to deliver the goods.

There’s a lot in store for this week, so let’s get into it:

Seeing Like a State

I’ve been deep in James C. Scott’s Seeing Like a State lately, so I wanted to riff this week on Scott’s notion of “legibility,” the book’s central idea. His thesis in SLAS is that central authorities impose top-down, mandated designs on societies in order to make them easier to understand through simplification and optimization techniques. Examples in the book range from scientific forestry and naming traditions to urban planning and collectivist agriculture.

Scott calls this ideology “authoritarian high modernism,” wherein governments, driven by a zealous belief in knowledge and scientific expertise, determine they can restructure the social order for particular gain: higher crop yields, more compliant citizenry, more efficient cities, or crime-free neighborhoods (a dangerous proposition when a “crime” is redefined at will by authorities). He’s ruthlessly critical of these ideas, as evidenced by the book’s subtitle, and presents dozens of cases of top-down-design-gone-wrong, the most extreme case being the Soviet Union’s collectivization program that led to widespread famine.

An interesting factor to think about is how and when to apply intentional design in service of legibility and control. It’s not an all good–all bad proposition, to be sure. Even though Scott levels a pretty harsh review of high modernist ideology, even he acknowledges its value in small, targeted doses for specific problems.

Legibility: A Big Little Idea

I linked to a piece a while back by Venkatesh Rao, the source where I first learned of Scott’s work.

The post is largely an introduction to the book’s themes, but adds a few interesting notes on the psychology behind legibility. Given all the history we have that demonstrates the failure rate of high modernist thinking, why do we keep doing it?

I suspect that what tempts us into this failure is that legibility quells the anxieties evoked by apparent chaos. There is more than mere stupidity at work.

In Mind Wide Open, Steven Johnson’s entertaining story of his experiences subjecting himself to all sorts of medical scanning technologies, he describes his experience with getting an fMRI scan. Johnson tells the researcher that perhaps they should start by examining his brain’s baseline reaction to meaningless stimuli. He naively suggests a white-noise pattern as the right starter image. The researcher patiently informs him that subjects’ brains tend to go crazy when a white noise (high Shannon entropy) pattern is presented. The brain goes nuts trying to find order in the chaos. Instead, the researcher says, they usually start with something like a black-and-white checkerboard pattern.

If my conjecture is correct, then the High Modernist failure-through-legibility-seeking formula is a large scale effect of the rationalization of the fear of (apparent) chaos.

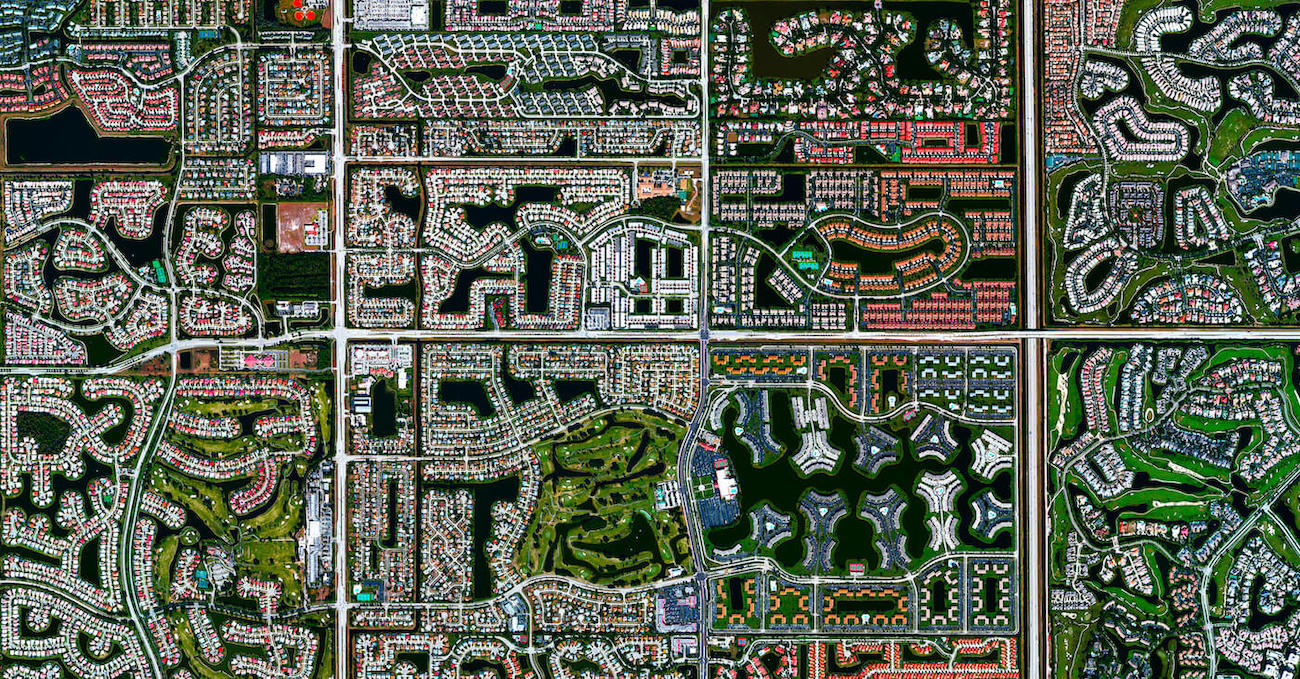

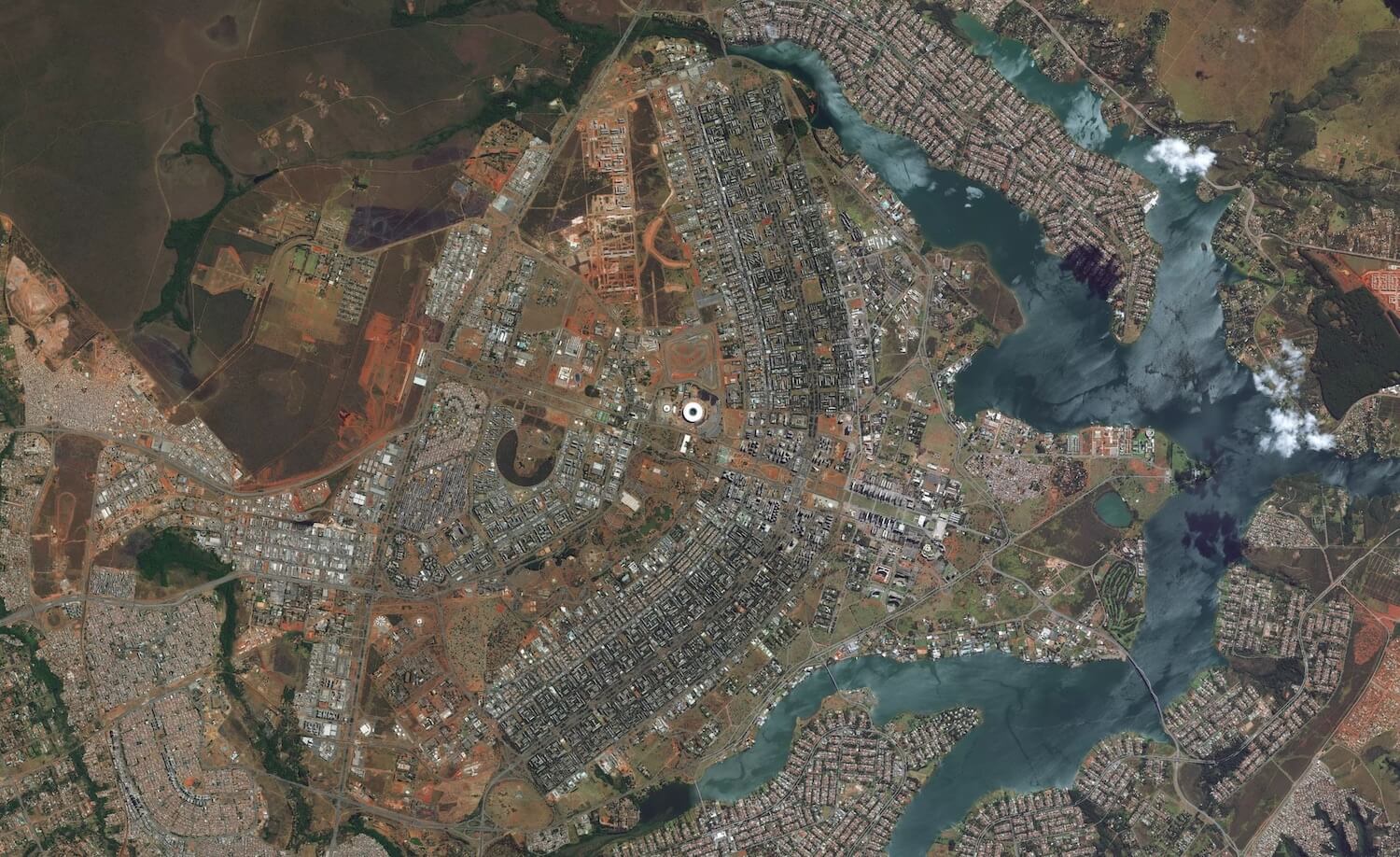

Scott also points out in the book how much of the high modernist mission is driven by “from above” aesthetics, not on-the-ground results. He analyzes the work of Le Corbusier and his visionary model for futuristic urban planning, most evident in his designs for Chandigurh in India and the manufactured Brazilian capital of Brasília (designed by his student, Lúcio Costa).

While Brasília projects a degree of majesty from above, life on the street is a hollowed-out, sterile existence. Its design ignored the realities of how humans interact. Life is more complex than the few variables a planner can optimize for. It’s telling that both Chandigurh and Brasília have lively slums on their outskirts, unplanned neighborhoods that filled demands unmet by the architected city centers.

He juxtaposes the work of Le Corbusier with that of Jane Jacobs, grassroots city activist and author of The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Jacobs was a lifelong advocate of “street life,” placing high emphasis on the organic, local, and human-scale factors that truly make spaces livable and enjoyable. She famously countered the ultimate high modernist visions of New York City planner Robert Moses.

This contrast between failure in legible, designed systems and resilience in emergent, organic ones triggers all of my free-market priors. The truth is there is no “best” mental model here. Certain types of problems lend themselves well to top-down control (require it, in fact), and others produce the best results when markets and individuals are permitted to drive their own solutions. Standard timekeeping, transportation networks, space exploration, flood control — these are all challenges that are hard to address for a variety of reasons without centralized coordination.

Imposing legibility demands an appreciation of trade-offs. Yes, dictated addressing schemes and fixed property ownership documentation do enable state control in the form of taxation, conscription, or surveillance. But in exchange for the right degree of imposed structure, we get the benefit of property rights and land tenure.

Big Tech’s Legible Vision

Byrne Hobart touched on this idea in an issue of his newsletter. (The Diff is some of the best tech/business/investing writing out there, I highly recommend subscribing). He makes the point that wherever scale is required, abstraction and legibility are highly valuable. He calls up Scott’s usage of the term mētis, translated from the classical Greek to mean roughly “knowledge that can only come from practical experience.” The value of this local knowledge is Scott’s counter to legibility-seeking schemes: that practical knowledge beats the theoretical every time.

I like this point that Hobart makes, though, on seeking larger scale global maxima: that a pure reliance on the practical can leave you stuck in a local maximum:

But mētis is a hill-climbing algorithm. If it’s based on experience rather than theory, it’s limited by experience. Meanwhile, theory is not limited by direct experience. By the 1930s, many physicists were quite convinced that an atomic bomb was possible, though of course none of them had ever seen one. Because some things can’t be discovered by trial and error, but can be created by writing down some first principles and thinking very hard about their implications (followed by lots of trial and error), the pro-legibility side has an advantage in inventing new things.

He also brings up its implications in the modern tech ecosystem. The Facebooks, Googles, and Amazons are like panoptic overseers that can force legibility even on the most impenetrable, messy datastreams through machine learning algorithms and hyper-scale pattern recognition. The trade-off here may not be conscription (not yet anyway), but there is a tax. There’s an interesting twist, though: the tech firms have pushed these specialized models so far to the edge that they themselves can’t even explain how they work, thereby reconstituting illegibility:

Fortunately for anyone who shares Scott’s skepticism of the legibility project, the end state for tech ends up creating a weird ego of the mētis-driven illegible system we started with. The outer edges of ad targeting, product recommendations, search results, People You May Know, and For You Page are driven by machine learning algorithms that consume unfathomable amounts of data and output a uniquely well-targeted result. The source code and the data exist, in human-readable formats, but the actual process can be completely opaque.

Functional versus Unit Organizations

While legibility interests me in its applicability to society as a whole, I’m even more intrigued by how this phenomenon works on a smaller scale: within companies.

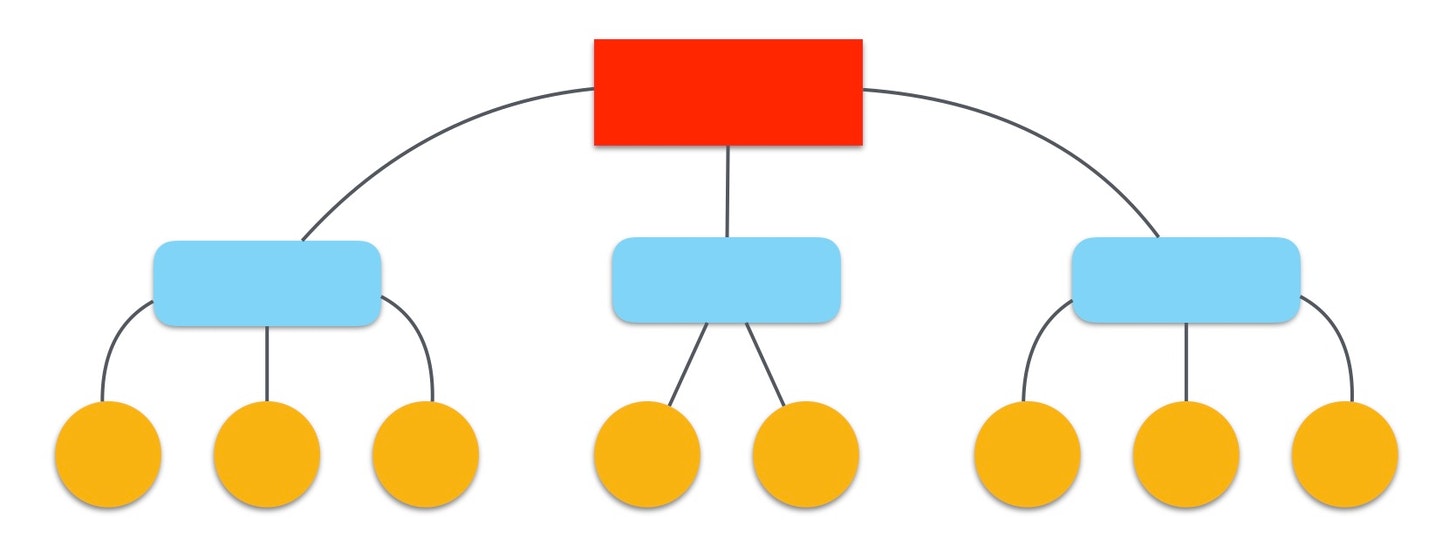

Org charts attempt to balance productivity and legibility, which often pull in different directions. Organizational design is driven by a hybrid need:

- To ship products and services to customers in exchange for revenue and equity value, and

- To be able to control, monitor, and optimize the corporate machine

Companies spend millions each year doing “reorgs,” often attributing execution failures to #2: the illegibility of the org’s activities. Therefore you rarely see a reorg that results in drastic cutback of management oversight.

Former Microsoft product exec and now-VC Steven Sinofsky wrote this epic piece a few years back comparing the pros and cons of function- and unit-based organizational structures. Each has merits that fit better or worse within an org depending on the product line(s), corporate culture, geographic spread, go-to-market, and headcount. The number one objective of an optimum org chart is to maximize value delivery to customers through cost reduction, top-line revenue gains, lower overhead, and richer innovation in new products. But legibility can’t be left out as an influence. The insertion of management layer is an attempt to institute tighter control and visibility, a degree of which is necessary to appropriately dial-in costs and overhead investment.

Look at this statistic Sinofsky cites about the Windows team’s composition when he joined:

One statistic: when I came to Windows and the 142 product units, the team overall was over 35% managers (!). But the time we were done “going functional” we had about 20% managers.

Even corporate teams aren’t immune to the pull of legibility. When its influence is stretched too far, you end up with Dilbert cartoons and TPS reports.

Emergent Order in Cities

It was serendipitous to encounter this same theme in Devon Zuegel’s podcast, Order Without Design. The show is a conversation with urbanist Alain Bertaud and his wife Marie-Agnes, an extension of his book on urban planning and how “markets shape cities.”

In episode 3 they discuss mostly sanitation and waste management in cities around the world, but my favorite bit was toward the end in a discussion on how different cities segment property into lots and dictate various uses through zoning regulation. Some cities slice property into large lots, which leads to fewer businesses and higher risk for large, expensive developments. But others, like Manhattan, segment into smaller chunks, resulting in a more diverse cityscape that mixes dining, retail, services, and many other commercial activities.

The shopping mall was an innovation that allowed developers with limited local knowledge to have tenants respond to customer demand in smaller, less risky increments. Malls in Asia notably differ from ours in the west in the breadth of goods and services they typically offer. Here’s Marie-Agnes from the episode:

…Remember the Singapore mall. In Singapore the malls have not only retail, but you find also dental offices, notaries, kindergarten schools, dispensaries, and all sorts of activities. Up to now and in general the concept of a mall in the US is for mainly shopping. You may have food court and some restaurants, but nothing like a real city where you have all sort of business.

Devon points out that this quality might make these malls more resilient to market stress than our retail-focused American versions.

Malls are by no means a modern innovation, of course. Ad-hoc congregations of commercial activity have been around for 5,000 years, evolving from purely organic bazaars of the Near East into the pseudo-planned, air conditioned behemoths we have today. Even in our technocratic culture, planners still realize that the flexibility to market demand is crucial to sustainability. Trying to pre-design and mandate a particular distribution of stores and services is a fool’s errand.

In Byrne’s newsletter, he says “once you look for legibility, you start to see it everywhere.” This has certainly been true for me as I’ve been reading Scott’s work. The deepest insights are the ones that cut widely across many different dimensions.

There’s no silver bullet in how to apply legibility-inducing schemes to any of these areas. But until you’re aware of the negative consequences, there’s no way to balance the scales between legible/designed and illegible/organic outcomes.