Outcomes Don't Look Like We Predict

October 12, 2023 • #Just because we set an objective doesn’t mean we’ll reach it. At least not in the specific form we imagine.

When we do finally reach a destination that’s descriptively similar to the objective we thought we were after (artificial intelligence, augmented reality, flight, fusion, et al), it will look wildly different in practice than we thought.

Once we achieve a breakthrough innovation, along the path of stepping stones — the series of building blocks we must pass through to get us there — we’ve made hundreds of additional observations on the journey that change what we thought we wanted.

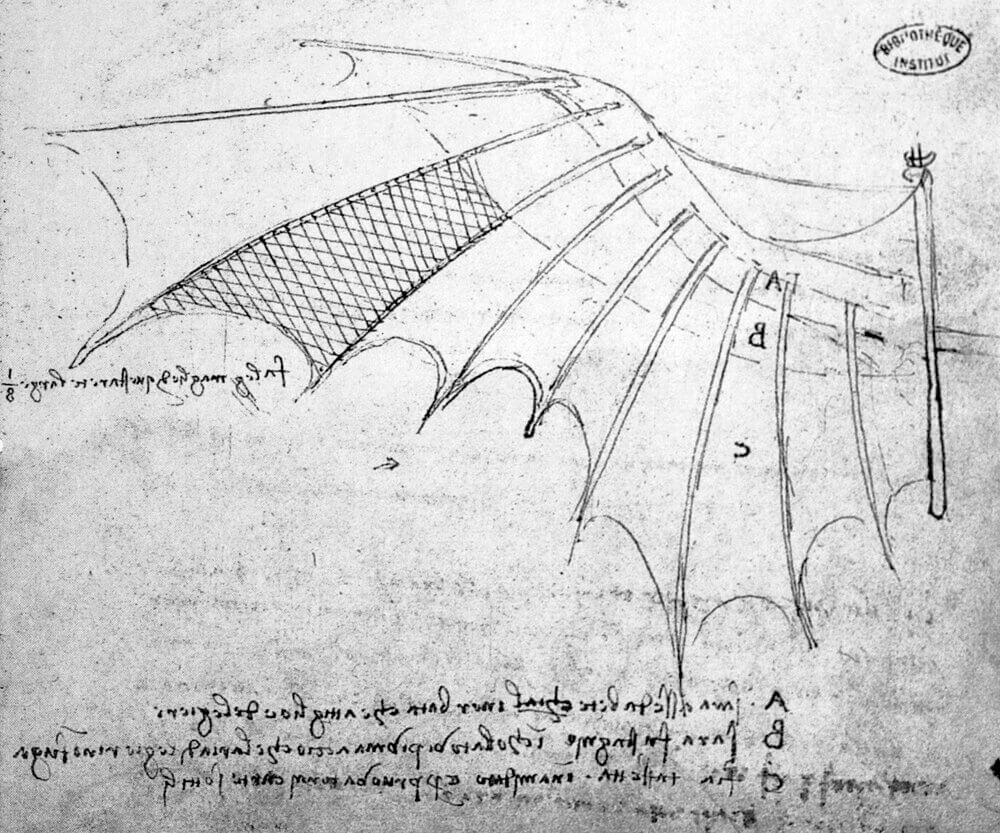

The first aspiring aviators mimicked the flapping of a bird’s wings in their designs. Take a look at Da Vinci’s notebook illustrations and you’ll get a sense for where conventional wisdom was at the time on how flight might be one-day achieved.

But along the way, through continuous iteration and discovery of the “adjacent possibles”, we learned that fixed wing flight was not only more attainable with the available late 19th century engineering techniques, but was also superior for manned, powered flight. A bird attains lift and propulsion through a flapping motion. But humans found a way to decouple the two, which meant we could use ever-more-powerful propulsion methods, and still rely on the same principle of aerodynamic lift.

Kevin Kelly calls these unpredictable destinations “movable futures”:

One of the reasons it is hard to predict what the future looks like is because much of the future is movable. The thing we are trying to forecast is changed by our attempts to make it real. Many hundreds of years ago, when creative people imagined flying machines, they imagined machines that had wings that flapped. What they imagined did not happen; the deliverable moved to an airplane with fixed wings. In the 1950s we imagined wrist-watch radios on every person in the future, and that did not happen (yet), but instead, the future moved to “radios” in the pocket of every person. Now we feel we don’t want wrist-watch radios. The future moved.

What we think we want at the beginning hasn’t yet been informed by all our learnings along the way.