October 10, 2022 • #

For any company, keeping track of your position in the competitive landscape is an important element of making the right decisions. When I think about competitors, I think about them separately as “direct” vs. “indirect”:

- Direct competitor: one with a product offering highly similar and seen by your customer as a direct substitute

- Indirect competitor: one that might look glancingly similar (or very different) on the surface, but addresses the same jobs to be done

Direct vs. indirect doesn’t matter all that much at the end of the day;...

✦

October 20, 2020 • #

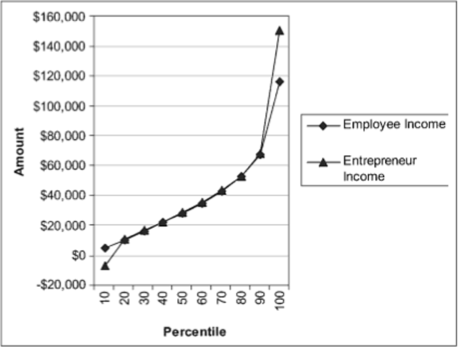

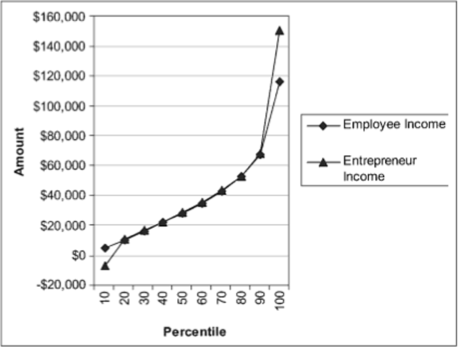

There’s a myth in popular culture that associates “being an entrepreneur” with “making a lot of money.” But do they, if compared to a world where an entrepreneur did the same job in the employ of someone else?

In this post, Jerry Neumann references a chart from Scott Shane’s The Illusion of Entrepreneurship that tells a much more realistic story of what creating your own business means financially:

The vast majority make the same, if not less than, their non-self-employed peers,...

✦

September 16, 2020 • #

Seems like every company claims to be harnessing some type of network effect in their business model.

This post goes in-depth at defining and comparing different forms of network effects, diagramming them in a radial pattern — from more to less defensible as you move outward. A helpful reference guide.

Most companies’ advantages aren’t cleanly put in a single bucket, the total picture of the business has factors in multiple boxes. This guide is a useful companion to Advantage Flywheels in describing business models.

✦

August 28, 2020 • #

In his article “Strategy Under Uncertainty,” Jerry Neumann contrasts the traditional Porter model of business strategy with one more suited to startups, the former being modeled around mature organizations operating in known competitive spaces, the latter around startups moving in opaque environments with higher uncertainty and more moving parts.

In the piece he defines “strategy” as a framework for “how to make decisions in situations that are not yet known.” To have a purposeful, intentional approach to an objective, whether in war, sports, or business, you have to formulate a model for predicting...

✦

July 29, 2020 • #

Ben Thompson published this piece a few weeks back on the state of Slack up against its competitive market for chat and collaboration, namely Microsoft’s Teams product. It covers the history well, dating back to Microsoft’s 2016 announcement of Teams, through to their traction, scale, and eventually overtaking of Slack in daily users on their platform.

We’re a Slack shop like many, but I’ve used Teams to join in on calls and it’s gotten darn good from what I can tell. The devil is, of course, in the details. I use Slack for hours a day and it’s become so second-nature...

✦