On Retention

July 12, 2019 • #Earlier this year at SaaStr Annual, we spent 3 days with 20,000 people in the SaaS market, hearing about best practices from the best in the business, from all over the world.

If I had to take away a single overarching theme this year (not by any means “new” this time around, but louder and present in more of the sessions), it’s the value of customer success and retention of core, high-value customers. It’s always been one of SaaStr founder Jason Lemkin’s core focus areas in his literature about how to “get to $10M, $50M, $100M” in revenue, and interwoven in many sessions were topics and questions relevant to things in this area — onboarding, “aha moments,” retention, growth, community development, and continued incremental product value increases through enhancement and new features.

Mark Roberge (former CRO of Hubspot) had an interesting talk that covered this topic. In it he focused on the power of retention and how to think about it tactically at different stages in the revenue growth cycle.

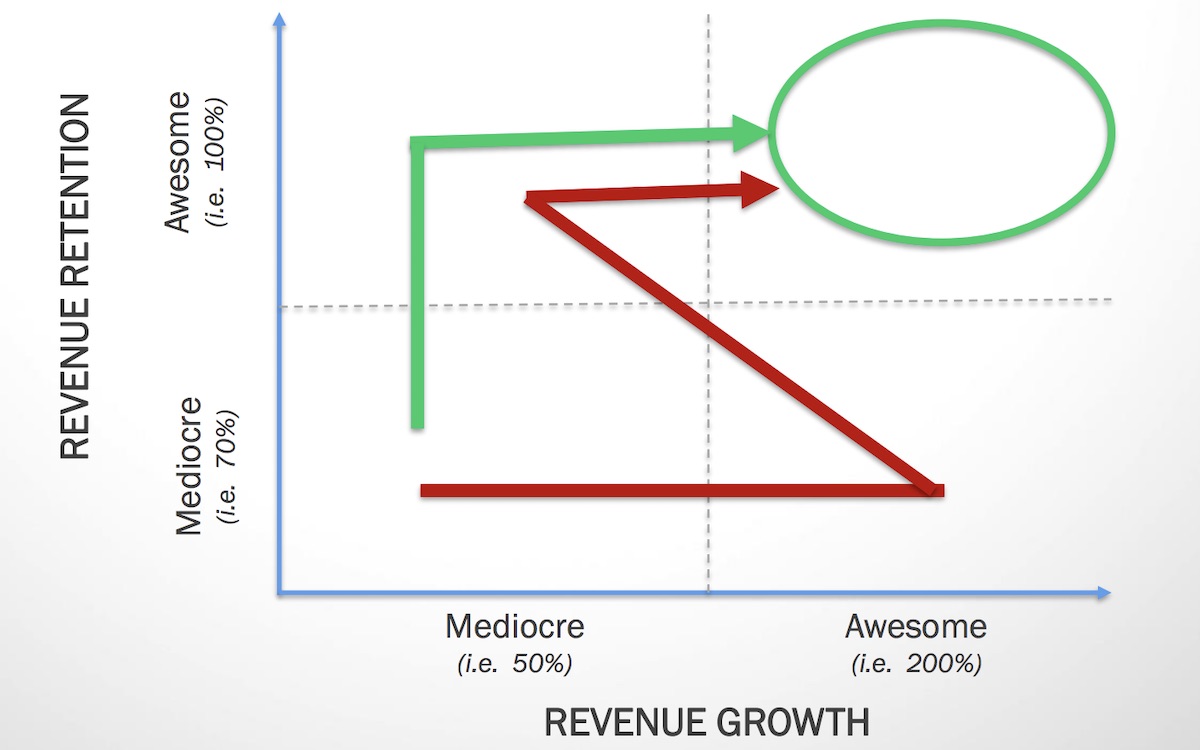

If you look at growth (adding new revenue) and retention (keeping and/or growing existing revenue) as two axes on a chart of overall growth, a couple of broad options present themselves to get the curve arrow up and to the right:

If you have awesome retention, you have to figure out adding new business. If you’re adding new customers like crazy but have trouble with customer churn, you have to figure out how to keep them. Roberge summed up his position after years of working with companies:

It’s easier to accelerate growth with world class retention than fix retention while maintaining rapid growth.

The literature across industries is also in agreement on this. There’s an adage in business that it’s “cheaper to keep a customer than to acquire a new one.” But to me there’s more to this notion than the avoidance of the acquisition cost for a new customer, though that’s certainly beneficial. Rather it’s the maximization of the magic SaaS metric: LTV (lifetime value). If a subscription customer never leaves, their revenue keeps growing ad infinitum. This is the sort of efficiency ever SaaS company is striving for — to maximize fixed investments over the long term. It’s why investors are valuing SaaS businesses at 10x revenue these days. But you can’t get there without unlocking the right product-market fit to switch on this kind of retention and growth.

So Roberge recommends keying in on this factor. One of the key first steps in establishing a strong position with any customer is to have a clear definition of when they cross a product fit threshold — when they reach the “aha” moment and see the value for themselves. He calls this the “customer success leading indicator”, and explains that all companies should develop a metric or set of metrics that indicates when customers cross this mark. Some examples from around the SaaS universe of how companies are measuring this:

- Slack — 2000 team messages sent

- Dropbox — 1 file added to 1 folder on 1 device

- Hubspot — Using 5 of 20 features within 60 days

Each of these companies has correlated these figures with strong customer fits. When these targets are hit, there’s a high likelihood that a customer will convert, stick around, and even expand. It’s important that the selected indicator be clear and consistent between customers and meet some core criteria:

- Observable in weeks or months, not quarters or years — need to see rapid feedback on performance.

- Measurement can be automated — again, need to see this performance on a rolling basis.

- Ideally correlated to the product core value proposition — don’t pick things that are “measurable” but don’t line up with our expectations of “proper use.” For example, in Fulcrum, whether the customer creates an offline map layer wouldn’t correlate strongly with the core value proposition (in isolation).

- Repeat purchase, referral, setup, usage, ROI are all common (revenue usually a mistake — it’s a lagging rather than a leading indicator)

- Okay to combine multiple metrics — derived “aggregate” numbers would work, as long as they aren’t overcomplicated.

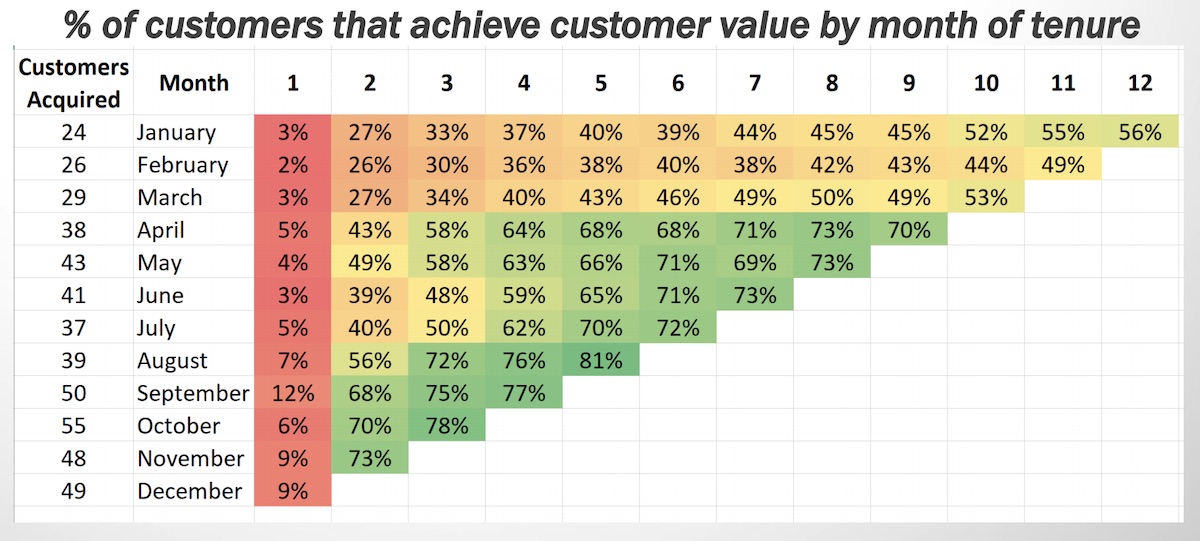

The next step is to understand what portion of new customers reach this target (ideally all customers reach it) and when, then measure by cohort group. Putting together cohort analyses allows you to chart the data over time, and make iterative changes to early onboarding, product features, training, and overall customer success strategy to turn the cohorts from “red” to “green”.

We do cohort tracking already, but it’d be hugely beneficial to analyze and articulate this through a filter of a key customer success metric is and track it as closely as MRR. I think a hybrid reporting mechanism that tracks MRR, customer success metric achievement, and NPS by cohort would show strong correlation between each. The customer success metric can serve as an early signal of customer “activation” and, therefore, future growth potential.

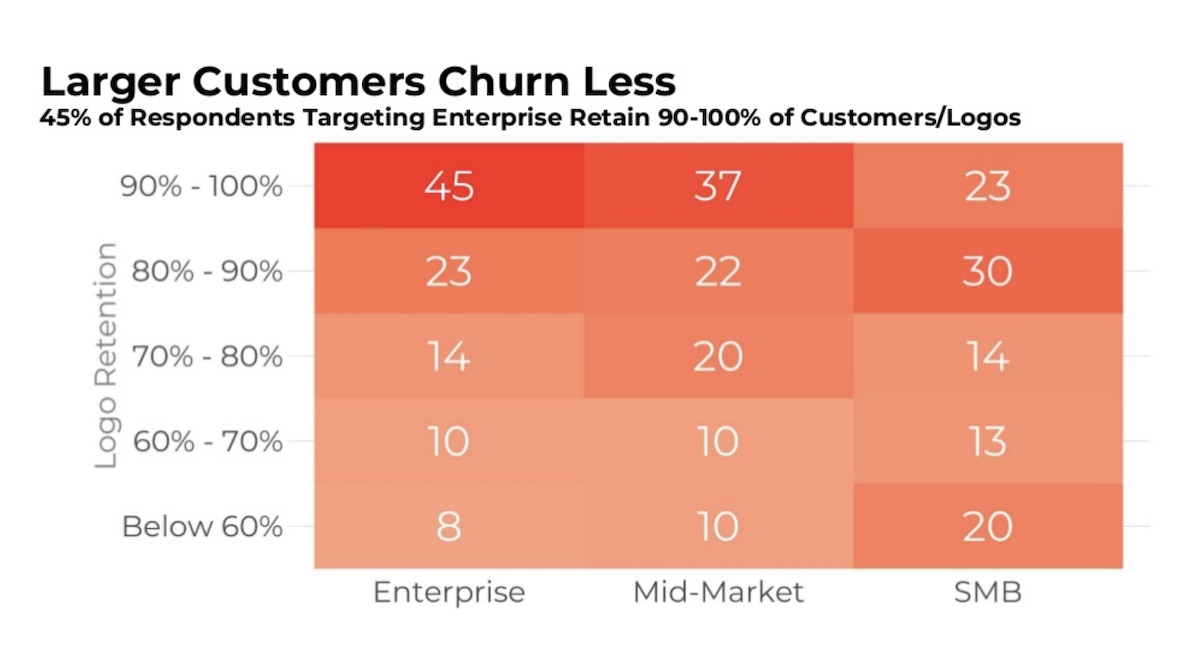

I also sat in on a session with Tom Tunguz, VC from RedPoint Ventures, who presented on a survey they had conducted with almost 600 different business SaaS companies across a diverse base of categories. The data demonstrated a number of interesting points, particularly on the topic of retention. Two of the categories touched on were logo retention and net dollar retention (NDR). More than a third of the companies surveyed retain 90+% of their logos year over year. My favorite piece of data showed that larger customers churn less — the higher products go up market, the better the retention gets. This might sound counterintuitive on the surface, but as Tunguz pointed out in his talk, it makes sense when you think about the buying process in large vs. small organizations. Larger customers are more likely to have more rigid, careful buying processes (as anyone doing enterprise sales is well aware) than small ones, which are more likely to buy things “on the fly” and also invest less time and energy in their vendors’ products. The investment poured in by an enterprise customer makes them averse to switching products once on board1:

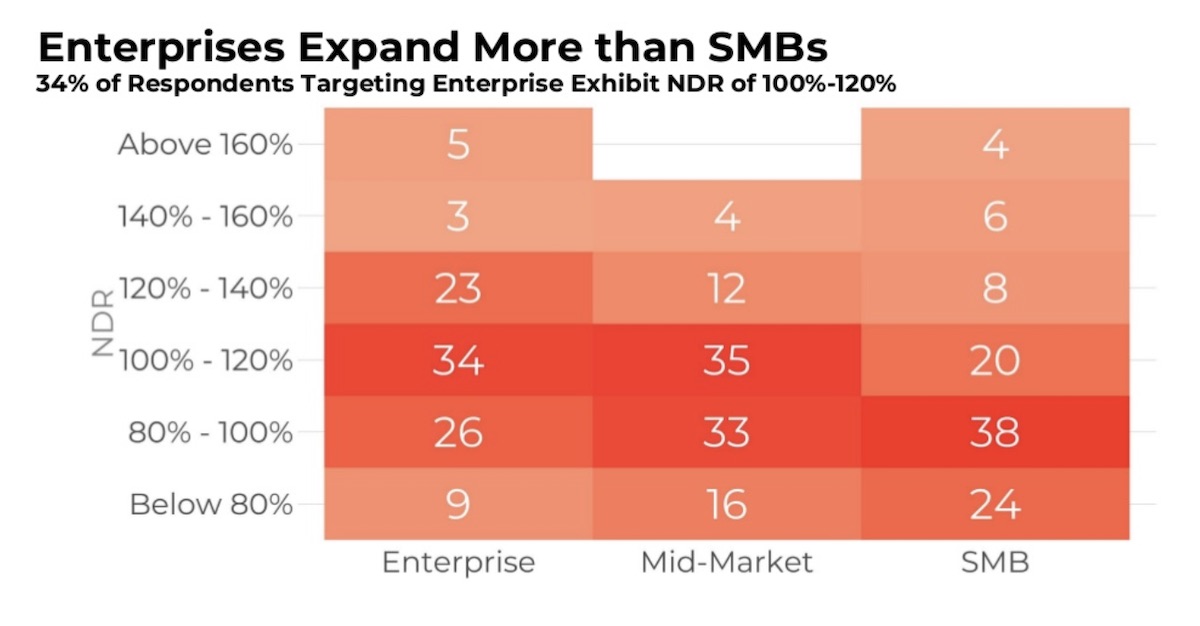

On the subject of NDR, Tunguz reports that the tendency toward expansion scales with company size, as well. In the body of customers surveyed, those that focus on the mid-market and enterprise tiers report higher average NDR than SMB. This aligns with the logic above on logo retention, but there’s also the added factor that enterprises have more room to go higher than those on the SMB end of the continuum. The higher overall headcount in an enterprise leaves a higher ceiling for a vendor to capture:

Overall, there are two big takeaways to worth bringing home and incorporating:

- Create (and subsequently monitor) a universal “customer success indicator” that gives a barometer for measuring the “time to value” for new customers, and segment accordingly by size, industry, and other variables.

- Focus on large Enterprise organizations — particularly their use cases, friction points to expansion, and customer success attention.

We’ve made good headway a lot of these findings with our Enterprise product tier for Fulcrum, along with the sales and marketing processes to get it out there. What’s encouraging about these presentations is that we already see numbers leaning in this direction, aligning with the “best practices” each of these guys presented — strong logo retention and north of 100% NDR. We’ve got some other tactics in the pipeline, as well as product capabilities, that we’re hoping bring even greater efficiency, along with the requisite additional value to our customers.

-

Assuming there’s tight product-market fit, and you aren’t selling them shelfware! ↩