On Markets, TAMs, and Agency

September 16, 2022 • #If you’ve been involved in investing or fundraising activities in the past, you’ve likely heard about “TAMs” (total addressable market), as in “So what’s your TAM look like?” The general idea is to determine a metric that communicates in few words the nature of a given market for a product or service. Investors want to know how a company thinks about its market opportunity (investors generally want large ones), and startup founders need to have a sense for what they can realistically target, build for, sell to, and capture to build a business. You may also have heard of TAM’s cousins, like SAM and SOM (serviceable addressable market and serviceable obtainable market), but let’s stick to the big one here.

TAM is part of the lingua franca of the fundraising process, a term thrown around casually and understood in a variety of ways by investors and operators alike. For those of us on the operator side of the table, calculating your TAM is a necessary part of the company-building and fundraising process. Most founders don’t start with the question of “What’s the biggest TAM I could target?” before starting on their idea. Picking apart the market specifics is typically downstream of prototyping an idea for a job to be done. As a founder you have to think about how to effectively communicate just enough here to be useful to the audience. But how is TAM useful? What is an investor doing with those numbers beyond saying “Yep, this is big enough”?

What TAM analysis is good for

Firstly, a TAM serves to communicate how a company thinks about its target customer. Let’s say you build a team collaboration tool for cross-company projects. Who are the targets? What size companies? Is there a narrower industry focus? Generally the wider your target, the harder it will be to convincingly portray a useful TAM. Simply saying “anyone on Earth could be a customer, our TAM is $500 trillion” won’t persuade anyone, not to mention you’ve got quite the uphill battle to build and sell to such a broad audience. Being narrower isn’t a flaw, it’s a feature.

Which brings me to the second use for TAM: signaling the quality of your thinking about your business. A thoughtful, concise TAM analysis functions not only as a means to convey who your target is, but also as a sign of how thoroughly you’ve thought about the prospects of the business itself, meaning how to tackle a go-to-market. If you can tell a persuasive story about your target market, it lends credibility to why an investor should trust you with their money. A sloppy, or overconfident, or poorly-articulated market description (even if you have a baller product) doesn’t reassure anyone that you’ll be a good steward of the dollars. It’s like some people say about college degrees: they’re useful as signals of wherewithal and commitment as much as they are on their own merits of intelligence. They signal that you see something through to the end, a quality in higher demand by some employers than whether you have a BS in physics or a BA in philosophy.

But enough about the reasons why TAM matters. Let’s cover some reasons it’s not very useful, at least beyond a “qualifying variable” stage.

Then what’s wrong with TAMs?

Well, nothing is “wrong” with them, but they are quite often overvalued. For investors, how you read a TAM analysis and what emphasis to place on it is something to be circumspect about.

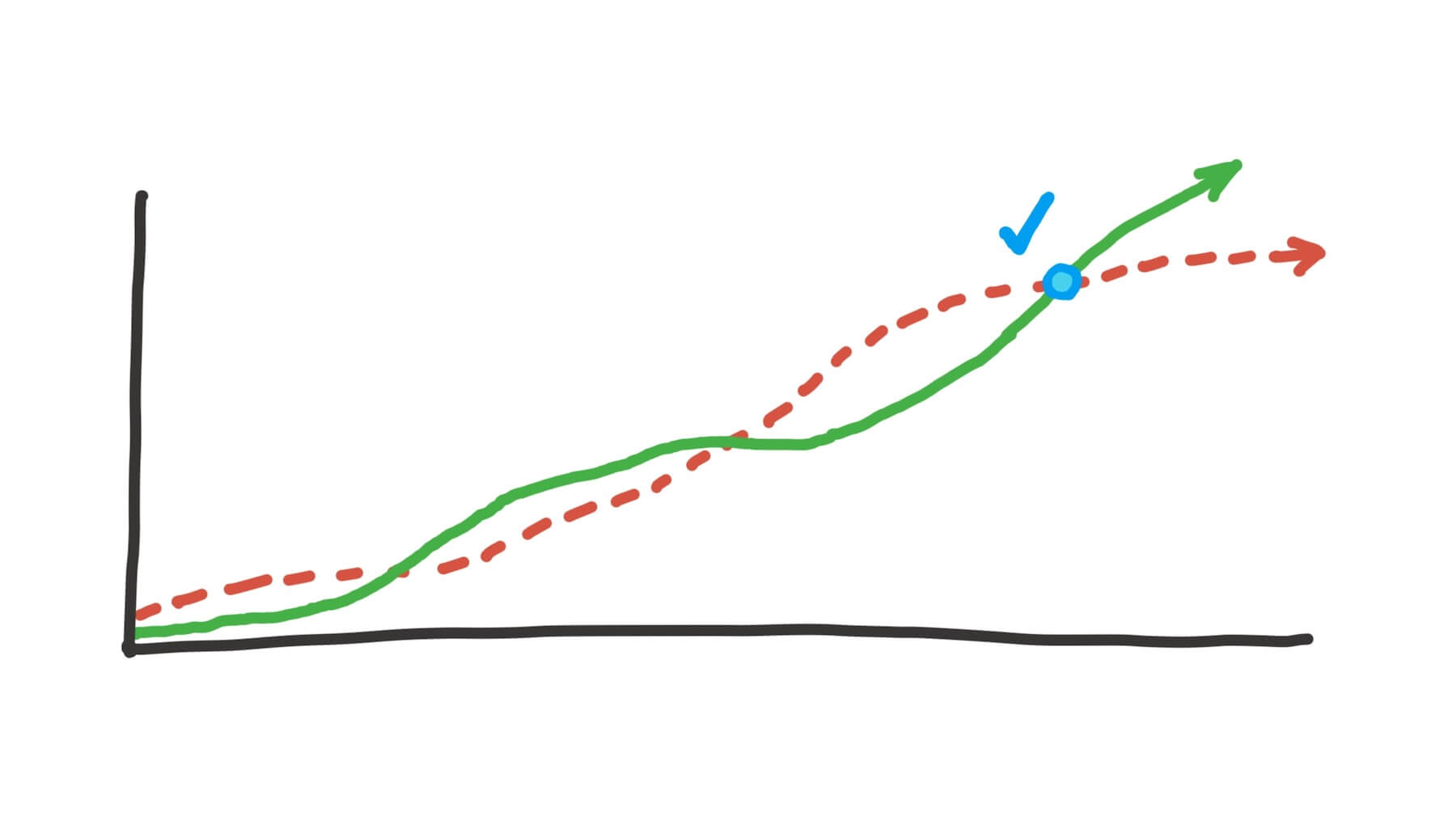

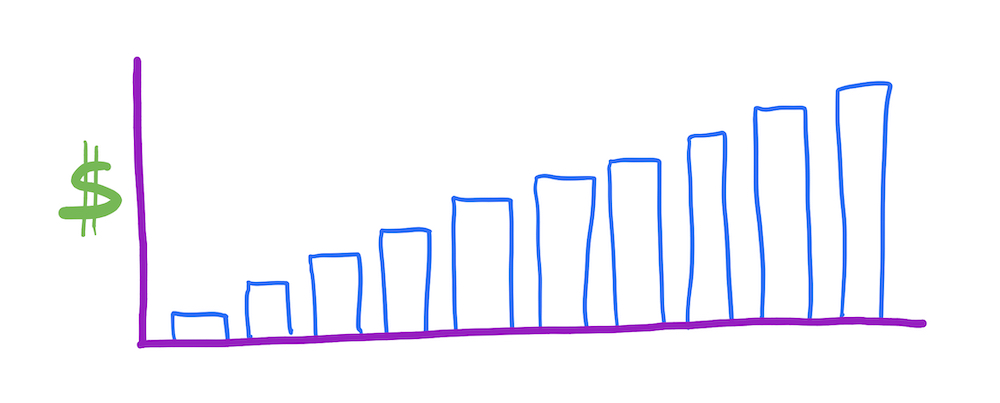

For one, markets aren’t static fixtures; they move, expand, and contract all the time. They’re moving targets. Sure, even with an understanding of this factor, a TAM can be useful as a snapshot in time as it stands the moment a deal is getting done. Even well-defined categories move all over the place. It’s more informative to look at it directionally — whether the market is expanding, or if it’s shrinking or being subsumed by an adjacent one.

Some of the best startups are great precisely because they’re targeting a strange combination of submarkets, or they’re in the early stages of creating a category, where there isn’t even an agreed-upon way of describing it yet. Conjuring TAMs for startups like this involves a mixture of alchemy and storytelling that can sometimes be unconvincing in the early days1.

For example, I’ve been building a low-code platform for field service organizations since 2011, but I’d never heard the term “low-code/no-code” (and we didn’t use it) until the mid-2010s sometime. Had we oriented on the “TAM” of no-code back then, what would we have determined? If you could even define a known boundary around the category at that time, it was probably in the 10s of millions or maybe $100 million total. Now the market is expanding at a CAGR of 30%, headed north of $180 billion by 2030, from around $10 billion in 2019. This market became a known one gradually over time. Initially it was just an undifferentiated, messy mass of people and companies doing things that looked similar to one another with app-builder tools, WYSIWYG editors, and pluggable integrations. Over time the ecosystem became legible and better understood, and now it’s a named category tracked by the likes of G2 and Gartner. But, importantly, some of the best investments in the space happened long before analyst acknowledgement. These are lagging indicators if you’re looking to be the first in, funding the most exciting new ideas.

But an even more important reason why TAMs are dangerous is that even if a market itself is relatively stable over time, your company doesn’t need to be stable. A company has agency. A great product team doesn’t stand still and let their market “happen to” them. Dimitri Dadiomov nails it here — couldn’t have said it better myself:

Part of the calculus with investing in an early product is measuring the future potential of the founders and the company. How a TAM is computed given the current status of a market, or the fitness of a product to said market, is irrelevant to capturing the future potential. A great product team will not stand by and let a better market, or a more focused market pass them by. In the best instances of this, in fact, startups can be singularly responsible for (or close to it) the creation of a market from whole cloth. Or at minimum they can greatly accelerate the realization of latent, obscured demand. Think iPad for tablet devices, Dropbox for personal cloud storage, Salesforce for CRM.

All of this is largely academic if you’re researching your market size to communicate with stakeholders. Take these tips for sizing and refining your definition and run just enough with them to communicate clearly. Just be wary not to internalize too directly the left and right bounds of your market. That’s not to say that defining ideal customer profiles is a bad thing… Far from it! But there’s a difference between “Alex here is the type of persona we’re building for” and “Our market is X big, and defined in this specific way.” Taking to heart what your market looks like without appreciating your own ability to change it can drive fatalistic behavior on the team. If your success in a market is flagging, or you’re making discoveries that the go-to-market angles into a specific customer set aren’t working, you have the steering wheel. You can change course, experiment your way into new markets, and make your TAM simply a snapshot of where you are, not a strict destiny.

-

But the great angel and seed investors pride themselves on the ability to conjecture about a founder or an idea’s prospects. ↩