Measuring Productivity

Florent Crivello had a short thread on Twitter contrasting the effectiveness on systems between Goldratt’s The Goal and Bill Walsh’s The Score Takes Care of Itself. One of the replies linked to this piece from Scott Young I found interesting for a couple of points on measuring productivity of systems.

The idea in books like The Goal and its modern IT counterpart The Phoenix Project present the process management paradigm of the Theory of Constraints. The shortest possible version of the TOC says that the output of a process or system is limited to the volume permitted through its narrowest constraint — a chain is only as strong as its weakest link. You could increase the efficiency, quality, or speed of all the remaining steps and not increase overall output if you’ve got a bottleneck.

This post first debates whether you’re better off measuring inputs or outputs to determine a system’s effectiveness. Books like The Goal seem to state that it’s all about the output; outcome over everything else; ends versus means. But Young makes the point that measuring only outputs is often not granular enough in complex systems to tie the application of a new technique or system to the change in outcome:

I’ve met a few consultants that have the following business model: I help you implement some idea for your business. If profits go up, you pay me a percentage. If they don’t, you don’t owe me anything. Win-win, right?

The trick is that businesses with volatile income will have many ups and downs. Most of that is random noise. Now imagine a consultant shows up with worthless advice—pure placebo effect. Half the businesses he consults go up, and he gets a hefty cut of the upside. Half go down, and he gets nothing. He makes a fortune, even though the advice is worthless.

He also references the Hawthorne effect, a phenomenon in which individuals modify their behavior in reaction to awareness that they’re being observed. If a consultant comes in to implement a new process, or you make a new “expert” hire that starts changing things, and results get better, how do you know there’s a causal link? What if the act of bringing in the consultant or new hire was what spurred the uptick, not their “improvements”? (People start working harder when there’s a consultant coming around, or when there’s a new manager in their department)1

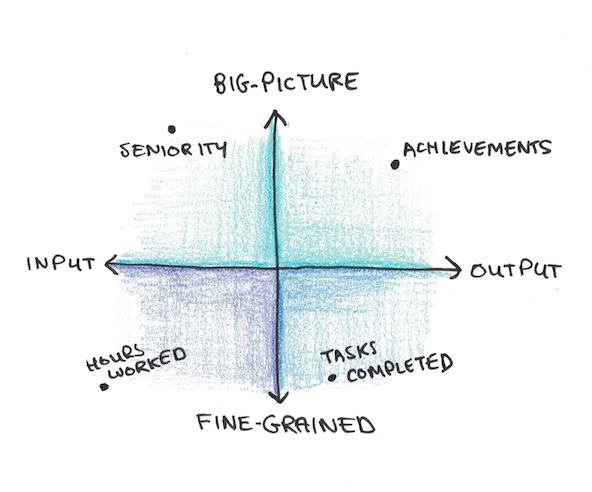

Another dimension orthogonal to input-output is scale — big, long-term items, or the activities happening at the individual task list level:

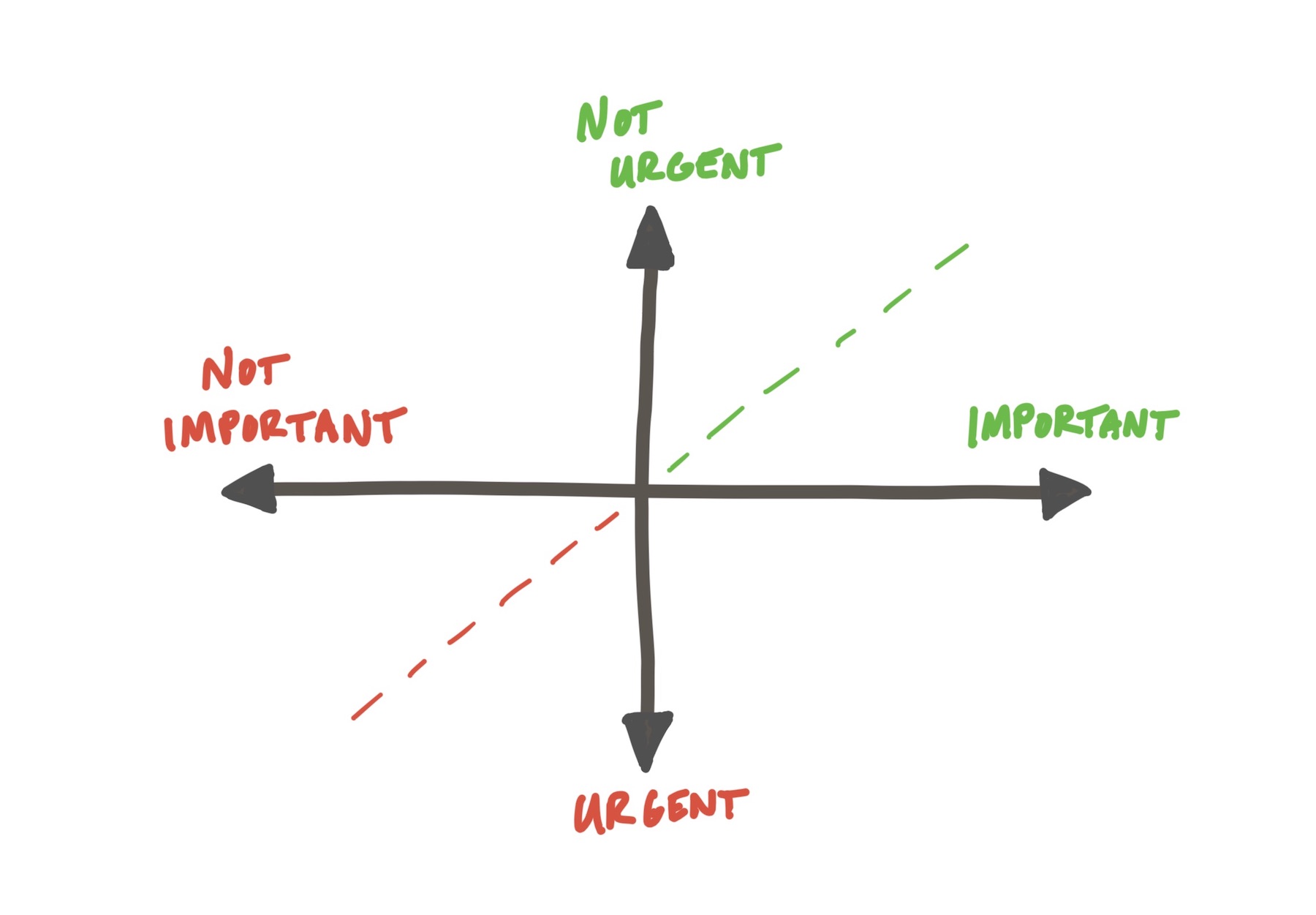

Plotted on two axes like this, I’m reminded of the Eisenhower Matrix for thinking about task priority:

Just like how with time management we want to orient ourselves toward the “not urgent / important” quadrant, in the productivity matrix we want to do things that push us toward the right spot in “big picture / output” quadrant. Not everything worth doing to position correctly on the scale-to-throughput chart falls in the same place. Just like with the TOC, bottlenecks exist at various stages and differ in levels of effort to widen or correct them. The “ROI” on a process change could by high-R, low-I, or the reverse. The effectiveness with which you can widen the bottleneck is often (but not always) decoupled from how much effort it takes.

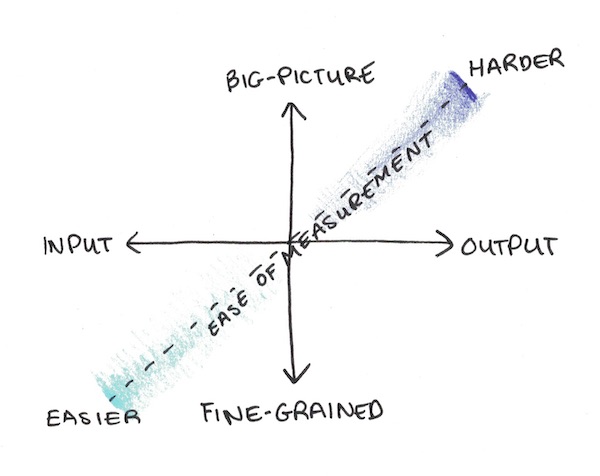

I like Young’s framing here on what to do and how to measure. If we’re seeking areas we can clearly measure, we know those are unlikely to be in the upper right quadrant. The lower left is great for aligning your measurements because of the clarity and speed possible at that scale. This is the best of the diagrams to explain a measurement strategy:

So as he says in the post: “pick a few metrics that will estimate what matters.” You want to figure out measurable items that directionally vector toward where you want to be — toward big outputs.

With a model like this, you can select tight, measurable metrics that aim the right direction, then make adjustments to course correct. Metrics that live in the lower left quadrants should have tight feedback loops, giving you signals on what adjustments are needed. Like all well-designed, robust systems, you want to build a productivity measurement model that’s adaptable, using trial and error to improve.

Check out Scott Young’s full post; it’s excellent.

-

I suppose through a purely outcome-driven lens, these examples got the desired outcome, regardless of how it was achieved. Though I don’t think in cases where this happens that anyone is savvy enough to realize true causes. ↩

Image credits: Scott Young