But the strongest prop of American order, Tocqueville found, was their body of moral habits. “I here mean the term ‘mores’ (moeurs) to have its original Latin meaning; I mean it to apply not only to “moeurs” in the strict sense, which might be called the habits of the heart, but also to the different notions possessed by men, the various opinions current among them, and the sum of ideas that shape mental habits.” Their religious beliefs in particular, and also their general literacy and their education through practical experience, gave to the Americans a set of moral convictions—one almost might say moral prejudices, as Edmund Burke would have put it—that compensated for the lack of imaginative leadership and institutional controls.

“It is their mores, then, that make the Americans of the United States, alone among Americans, capable of maintaining the rule of democracy; and it is mores again that make the various Anglo-American democracies more or less orderly and prosperous,” Tocqueville concluded.

“Europeans exaggerate the influence of geography on the lasting powers of democratic institutions. Too much importance is attached to laws and too little to mores. Unquestionably those are the three great influences which regulate and direct American democracy, but if they are to be classed in order, I should say that the contribution of physical causes is less than that of the laws, and that of laws less than mores… The importance of mores is a universal truth to which study and experience continually bring us back. I find it occupies the central position in my thoughts; all my ideas come back to it in the end.”

— Russell Kirk , The Roots of American Order →

Topic / history

103 postsWe do not merely study the past: we inherit it, and inheritance brings with it not only the rights of ownership, but the duties of trusteeship. Things fought for & died for should not be idly squandered. For they are the property of others, who are not yet born.

— Roger Scruton , How to Be a Conservative

Gratitude on the 4th of July

July 9, 2025 • #On being grateful for this weird and wonderful experiment.

Past, Present, and Future

April 10, 2025 • #A useful way of thinking about the domains of our three branches of government

We Live Like Royalty and Don't Know It

February 20, 2025 • #Charles Mann on the unseen, unappreciated wonders of modern infrastructure.

Western Electric Plant. Cicero, IL.

Western Electric was the captive equipment arm of the Bell System and produced the majority of the telephones and related equipment used in the U.S. for almost 100 years.

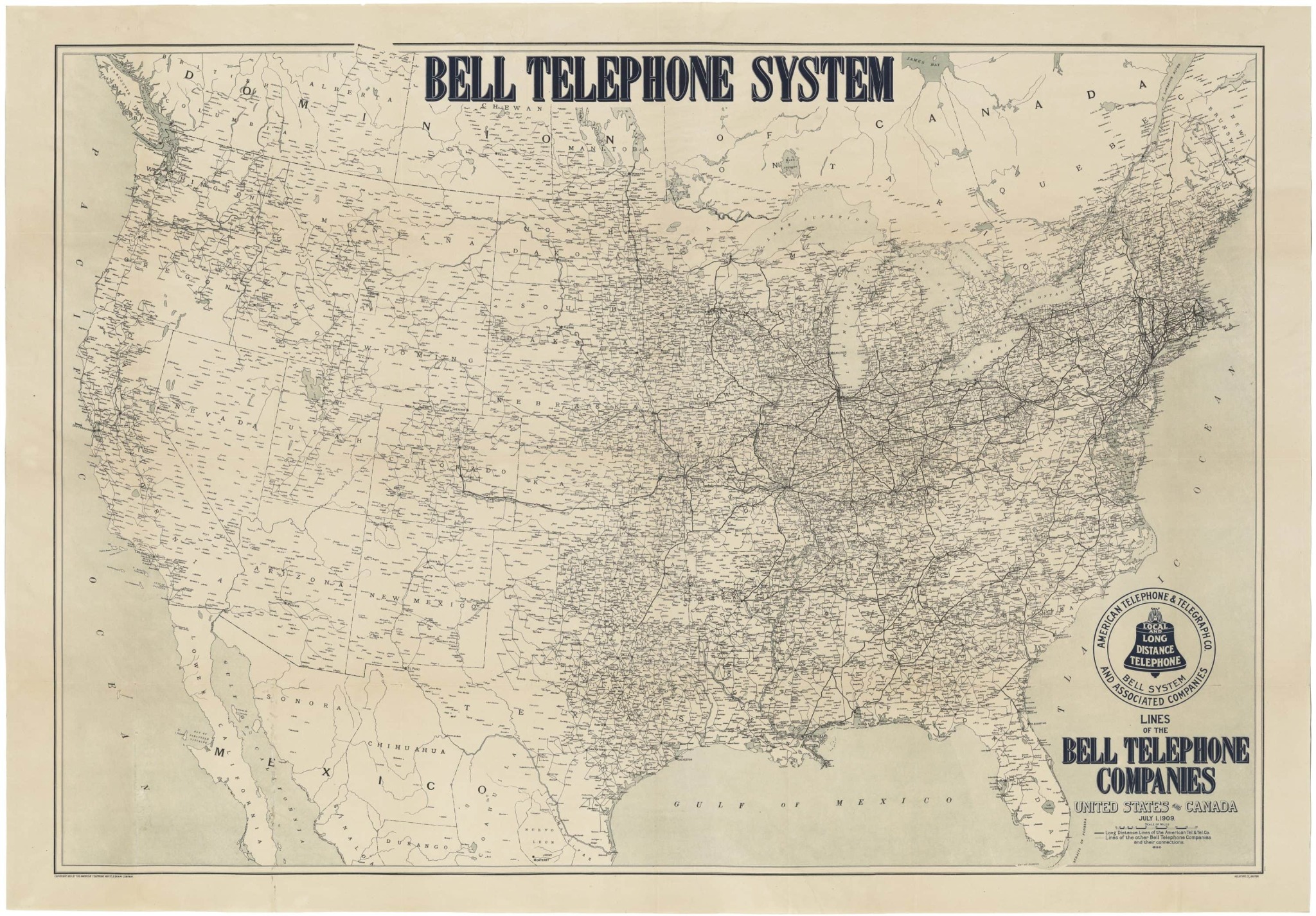

Map of the Bell Telephone System , 1909.

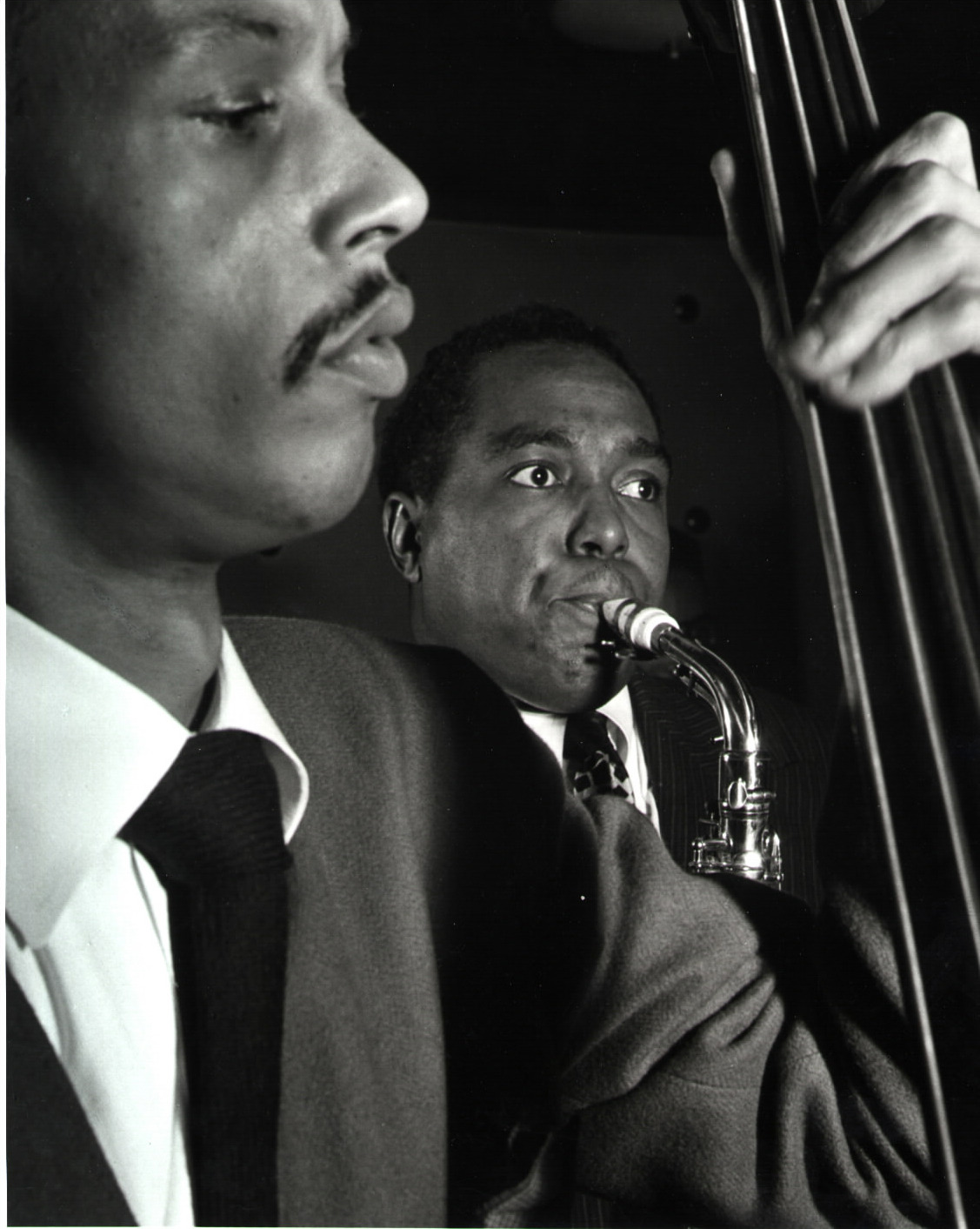

Bird absolutely locked in. Charlie Parker and Tommy Potter, 1947.

The Count and the Duke. Count Basie and Duke Ellington.

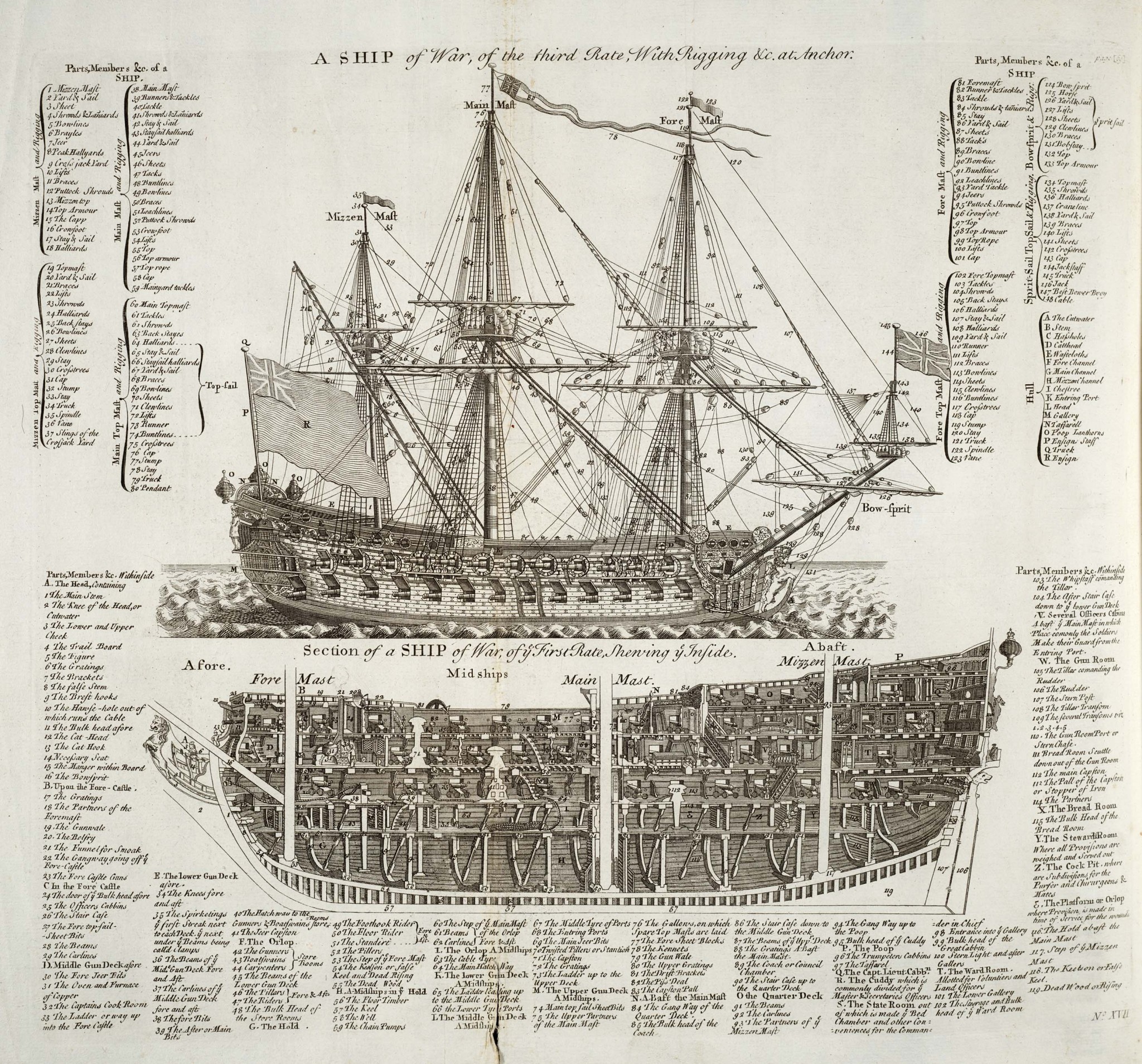

Diagram of a warship. From the Cyclopædia , 1728.

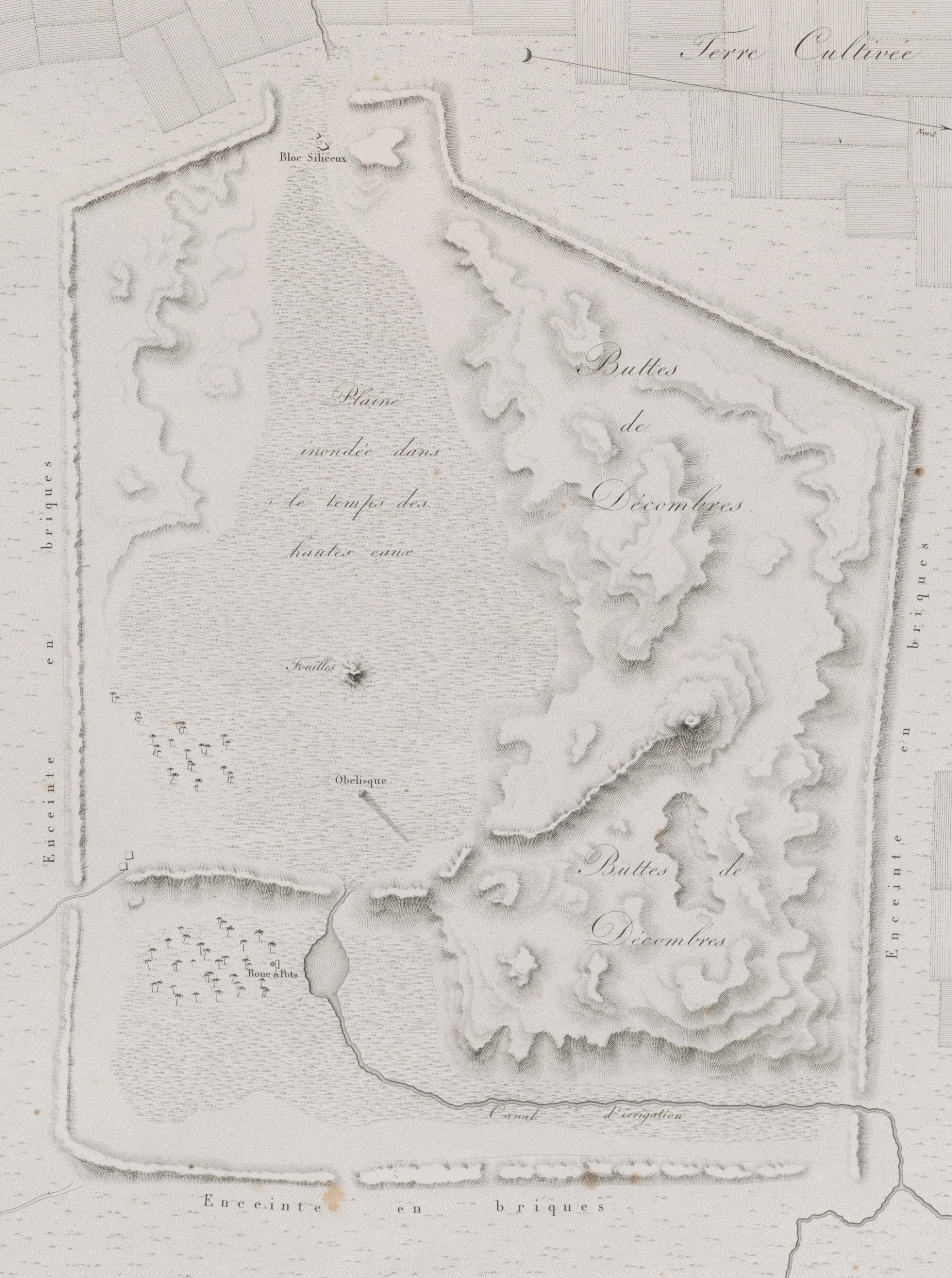

Temple des Eaux. Zaghouan, Tunisia.

Built by the Romans to supply the city of Carthage with water from its sacred spring. Visited in 2014.

The circle of the English language has a well-defined centre, but no discernible circumference.

In 2016 we visited Aubeterre in south France. This was inside of the subterranean monolithic Church of Saint-Jean , hollowed out of the mountainside in the 7th century.

Heliopolis , from Description de l’Égypte , 1809.

I just learned aboutbezoars andGoa stones (a man-made form of bezoar). It’s a chunk of aggregated minerals, seeds, piths, and other indigestible material that forms in the intestinal system of animals. People would shave off small bits and add to tea and beverages for medicinal purposes.

The way humans discover things without understanding why they work is endlessly fascinating.

Love this description:

The stones made their way to England as well and an early mention is made in 1686 by Gideon Harvey who was sceptical of the curative value noting that they were confected from a “ jumble of Indian Ingredients ” by “ knavish Makers and Traffickers.’ ”

The interior of Wrocław Cathedral , Poland. Built in 1272.

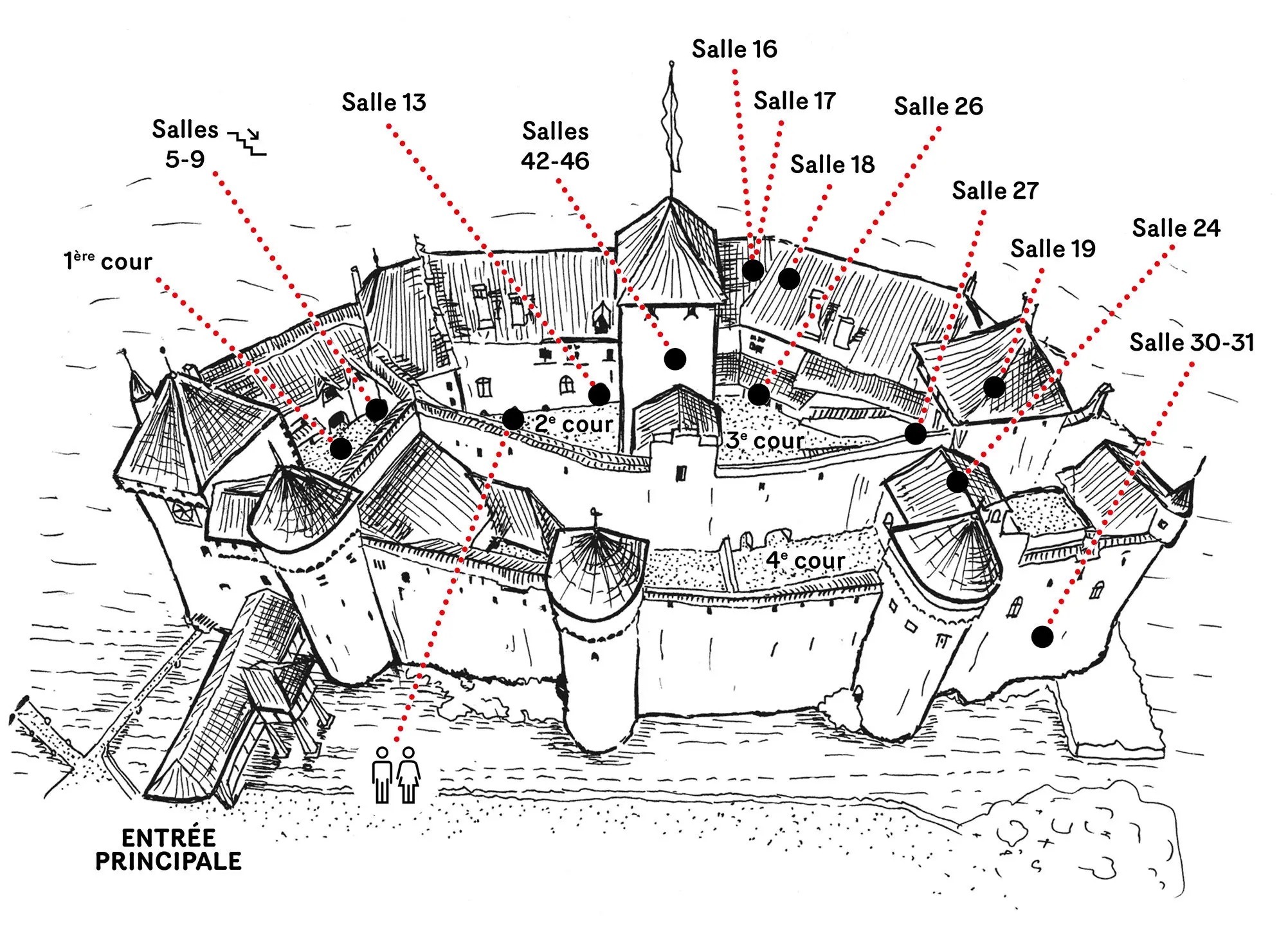

Chillon Castle , island fortress on Lake Geneva, Switzerland.

The building originally dates to the 11th century, but there’s evidence the Romans had forts on the small island a millennium earlier.

It’s functioned as fort, prison, and summer home to counts and dukes. Added to my one-day-Swiss-vacation list.

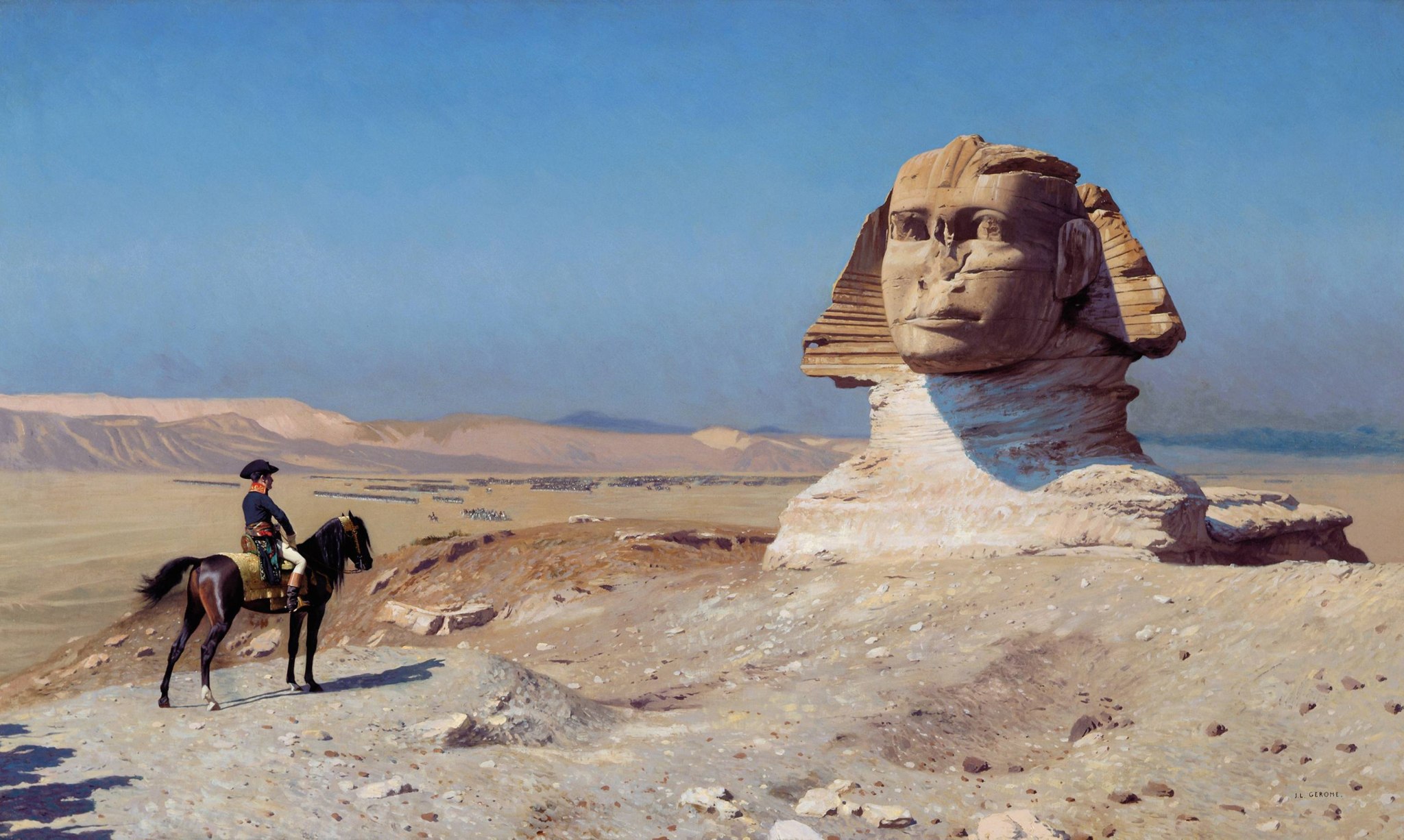

Bonaparte Before the Sphinx. Jean-Léon Gérôme, 1886.

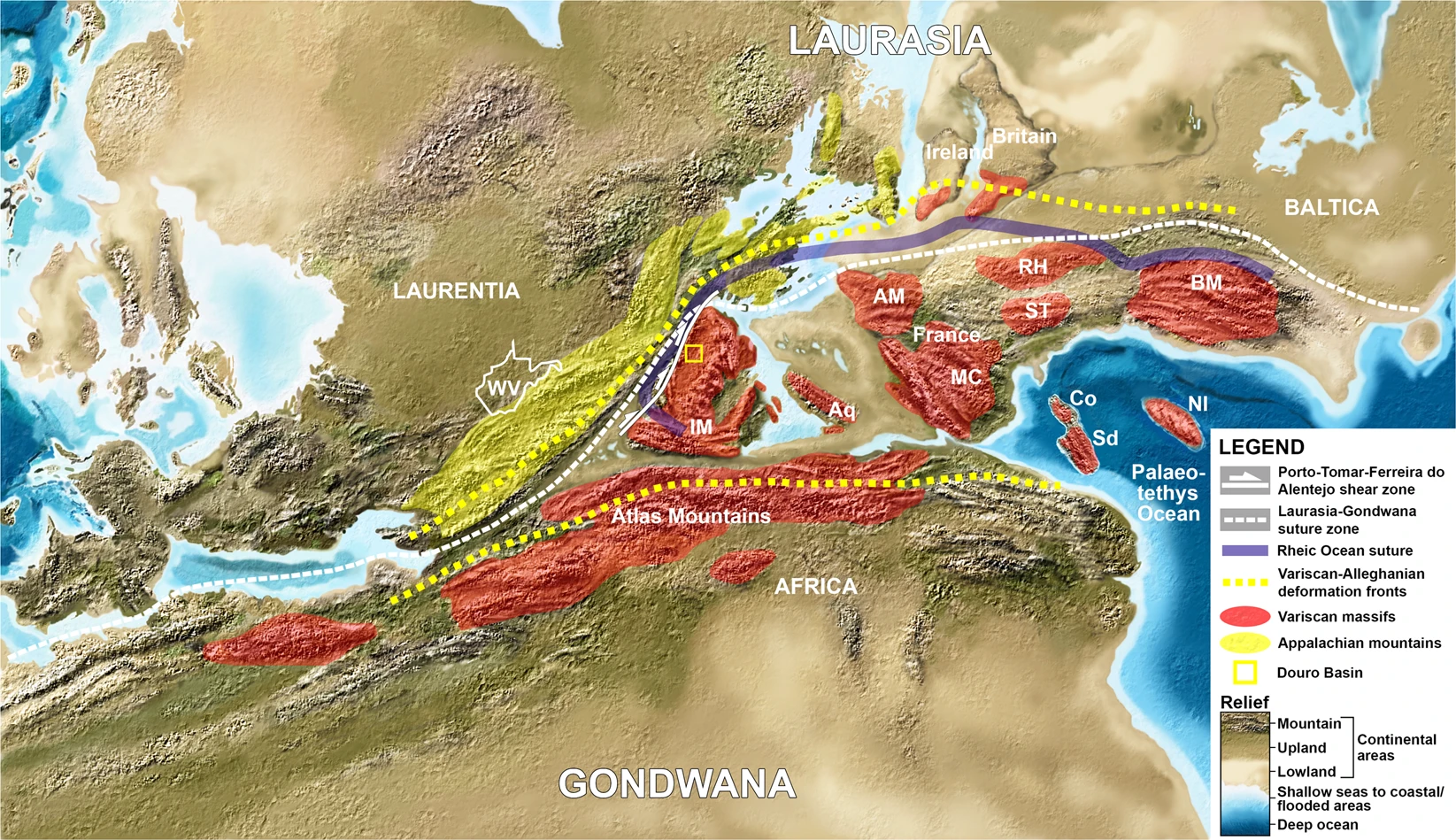

If you go back to the Permian, you’d find the Appalachians, Massif Central, Atlas Mountains, and Scottish Highlands were all part of a single range cutting through the Pangean supercontinent.

Europe and its fragmented city-state landscape of 1444.

See the full, zoomable hi-res version.

Lucerne’sKappelbrücke (Chapel Bridge) was built in 1360.

I got to walk across when I visited in 2014. Switzerland is like a 2-sided time warp: part medieval village, part urban futurescape.

Monthly Reading, August 2023

August 29, 2023 • #The 'improving mentality', how learning works, making decisions, the virtue of speed, and pattern languages

The Vesuvius Challenge

August 28, 2023 • #Developing AI methods to decode the Herculaneum scrolls.

Anachronistic History

August 24, 2023 • #ChatGPT teaches me some important historical events.

Areopagus

August 23, 2023 • #A newsletter on culture, art, music, and history.

Ancient Greek Terms

May 5, 2023 • #Ancient Greek terms we should restore to regular use.

The Rest Is History Podcast

April 10, 2023 • #My new favorite podcast.

Lessons from the Invention of the Thermometer

November 10, 2022 • #Invention requires the right combination of environment, timing, and purpose.

Popper on Great Man Theory

September 27, 2022 • #Great men are actually responsible for more tragic assaults on freedom than they are for human progress.

Regionalizing Renewable Energy

September 8, 2022 • #Can Europe turn an energy crisis into a positive renewable energy future?

Maxis 1996 Annual Report

August 26, 2022 • #A look back in time at Maxis, pioneers of the simulation game genre.

David McCullough Dies at 89

August 16, 2022 • #The death of legendary historian.

The Kalevala and the Underworld

August 5, 2022 • #An eerie similarity between an ancient Finnish myth and a deep geological nuclear repository.

Visa: The Original Protocols Business

May 5, 2021 • #The Business Breakdowns podcast looks at the history of Visa.

Hardcore Software

February 17, 2021 • #Steven Sinofsky's syndicated book on his time at Microsoft.

Weekend Reading: Digital Librarians, Tech Trees, and Alternate Histories in Maps

November 22, 2020 • #When to hire your first Chief Notion Officer, product roadmaps as tech trees, and maps of alternate histories.

A Reverse Dunkirk

November 6, 2020 • #What if the Germans had used a different strategy in 1940?

Weekend Reading: Non-Experts, Non-Linear Innovation, and We Were Builders

October 24, 2020 • #The rise of non-experts, innovation and linearity, and our history as builders.

Weekend Reading: American Growth, JTBD, and Dissolving the Fermi Paradox

October 17, 2020 • #Roots of Progress on The Rise and Fall of American Growth, a guide to JTBD interviews, and nullifying the Fermi paradox.

Intellectual Value

September 28, 2020 • #Esther Dyson's newsletter from 1994, on how intellectual property might work in the age of the internet.

Progress is Not Automatic

September 23, 2020 • #Innovation doesn't happen while we wait around, it's something that we choose to pursue, even if it doesn't always look that way.

Building a State

September 22, 2020 • #Anton Howes on the initial developments of state capacity in 16c Britain.

The Rise and Fall of the R&D Lab

August 31, 2020 • #Ben Southwood on what happened with the corporate research centers of the mid-20th century.

Weekend Reading: The First Corporation, Palantir, and Designing APIs

August 29, 2020 • #The birth of the joint-stock corporation, Palantir's S-1, and crafting APIs.

Why Maps Are Civilization's Greatest Tool

August 23, 2020 • #A review of some of the most important mapmaking achievements in history.

An Oral History of Deus Ex

July 23, 2020 • #Weekend Reading: Looking Glass Politics, Enrichment, and OSM Datasets

July 18, 2020 • #Gurri on private vs. public emotions, McCloskey on the boom of modern progress, and Facebook's work on OpenStreetMap data.

War, Revolution, Socialism

June 7, 2020 • #Stephen Kotkin looks back on the 1917 Russian Revolution.

SSC Reviews the Origin of Consciousness

June 4, 2020 • #Scott Alexander's review of the Origin of Consciousness.

Weekend Reading: Optionality, Pangaea, and Regulatory Disappointment

May 16, 2020 • #The trouble with optionality, modern day Pangaea, and when regulation goes wrong.

Innovation and Human Nature

May 10, 2020 • #Some brief thoughts in innovation, whether or not it's in our nature, and how mimetics might play a role.

History of Hip Hop, 1982

May 5, 2020 • #The Rub's 'History of Hip-Hop archives.

David Deutsch on Brexit and Error Correction

April 3, 2020 • #On resilience, error correction, Brexit, Karl Popper, and more.

Roots of Progress on Agriculture

March 31, 2020 • #Roots of Progress digs into the history of agriculture, with an open process.

Common Enemies

March 19, 2020 • #Morgan Housel on the similarities between COVID response and Allied mobilization in World War II.

Hardy Boys and Microkids

March 17, 2020 • #A review of Tracy Kidder's 1981 book, 'The Soul of a New Machine'.

On Building Systems That Will Fail

March 16, 2020 • #Fernando Corbato's 1990 talk about system complexity and the necessity for building in resilience.

Why Alto?

March 9, 2020 • #Butler Lampson's memo to the Xerox leadership, requesting investment in the Alto computer.

The UNIX System

March 5, 2020 • #Brian Kernighan, Dennis Ritchie, and Ken Thompson from Bell Labs on UNIX.

The Rise and Fall of Minicomputers

March 4, 2020 • #Weekend Reading: Figma's Typography, Xerox Alto, and a Timeline of CoVID

February 29, 2020 • #Figma's attention to typographic detail, restoring a Xerox Alto, and mapping the spread of CoVID-19.

Enter Ethernet

February 25, 2020 • #Bob Metcalfe's original schematic drawing of the ethernet spec.

RFC Reader

February 23, 2020 • #Browse and read RFCs.

10th Anniversary of the iPad: Perspective from the Windows Team

February 18, 2020 • #A look back at the iPad release from Steven Sinofsky.

The Deal of the Century

February 14, 2020 • #A history of the deal that moved Apple to the IBM PowerPC platform.

A Retrospective on the History of Work

February 11, 2020 • #A look at office life from the 1950s to 2000s.

Google Maps at 15

February 6, 2020 • #A history of Google Maps' development on its 15th birthday.

The Tech History Playlist

February 5, 2020 • #Creating a list of videos on tech history.

Adam Smith, Loneliness, and the Limits of Mainstream Economics

January 28, 2020 • #Russ Roberts on lonileness and accounting for the unmeasurable.

Man-Computer Symbiosis

January 24, 2020 • #JCR Licklider's 1960 paper.

Weekend Reading: Internet of Beefs, Company Culture, and Secular Cycles

January 18, 2020 • #Venkatesh Rao's theory of internet beef, the impacts of company culture, and Turchin's Secular Cycles.

Some Reflections on Early History by J.C.R. Licklider

January 17, 2020 • #JCR Licklider talk from the ACM conference, 1986.

Wernher von Braun and the Moon Landing

January 13, 2020 • #Scientist Wernher von Braun explains how we might one day reach the moon.

Weekend Reading: Bullets in Games, Lessons of History, and BrickLink

January 5, 2020 • #Bullet physics in games, notes from The Lessons of History, and BrickLink's Lego database.

Weekend Reading: The Worst Year to Be Alive, Chinese Sci-Fi, and Slack Networks

December 7, 2019 • #Why the 6th century was so miserable, the work of Ken Liu in spreading Chinese Sci-Fi, and Stewart Butterfield on Slack's shared channels.

The Mother of All Demos

November 24, 2019 • #Doug Engelbart's famous demo.

Microsoft Access: The Database Software That Won't Die

November 5, 2019 • #On the longevity of Microsoft Access.

Memos

October 25, 2019 • #Weekend Reading: Baseball Graphics, the Mind Illuminated, and the Crucial Century

October 19, 2019 • #Comparing baseball broadcast graphics, a review of The Mind Illuminated, and thinking about the most likely sites for the Industrial Revolution.

Why New Technology is Such a Hard Sell

October 16, 2019 • #The History of Steel

October 10, 2019 • #A presentation on the history of steel-making, from the SF progress studies meetup.

The All Things Tech History List

October 8, 2019 • #A great list of books, podcasts, movies, and more on the history of tech and Silicon Valley.

Age of Invention

October 6, 2019 • #A newsletter on innovation and the history of technological progress.

Instant Stone

September 26, 2019 • #Roots of Progress on the history of cement and concrete.

The Full Reset

September 19, 2019 • #On the power of starting with no baggage, sunk costs, or past poor decisions.

Steve Jobs in 1981

August 23, 2019 • #Steve Jobs on Nightline in 1981.

The Tunnel of Samos

August 7, 2019 • #Analyzing how the ancient Greeks constructed a kilometer-long water tunnel on the island of Samos.

Why Did We Wait So Long for the Bicycle?

July 22, 2019 • #Digging into the origins of the invention of bicycles.

Weekend Reading: Rhythmic Breathing, Drowned Lands, and Fulcrum SSO

July 20, 2019 • #Rhythmic breathing for impact reduction in running, drowned lands in Upstate New York, and SSO in Fulcrum

Cape Canaveral

June 23, 2019 • #Visiting Kennedy Space Center with the kids.

Five Lessons from History

June 9, 2019 • #Morgan Housel zooms out on how we can take away large, generalizable lessons from history.

The Second Phase: allinspections

June 3, 2019 • #A retrospective on my second product, allinspections.

A Spreadsheet Way of Knowledge

May 20, 2019 • #A history of the spreadsheet by Steven Levy, from 30 years ago.

Clippy: The Unauthorized Biography

April 28, 2019 • #Steven Sinofsky gives the history of Clippy, Microsoft's original assistant

Entering Product Development: Geodexy

March 27, 2019 • #A retrospective on the first product I worked on as (de facto) product manager: Geodexy, a predecessor to Fulcrum.

Weekend Reading: LiDAR, Auto Generated Textbooks, and Paleo Plate Tectonics

February 9, 2019 • #LiDAR, Auto Generated Textbooks, and Paleo Plate Tectonics

What Did the Earth Look Like?

January 15, 2019 • #An interactive map to see what the Earth looked like in prehistoric time.

The History of the World on One Map

January 14, 2019 • #Visualizing all of human history as a time lapse on a map.

Progress Report: The Federalist Papers

December 4, 2018 • #“Thoughts on the Federalist through essay

Spycraft

July 9, 2012 • #A review of 'Spycraft', a book about the OTS.

Counterinsurgency, a brief history

June 19, 2012 • #Thoughts on counterinsurgency doctrine.

Table Alphabeticall

October 7, 2011 • #Table Alphabeticall.

Early Washington

July 3, 2011 • #An impressive use of historic maps and data to rebuild the look of the Capital during its early years.